Resolution of the hypovolaemia is the primary concern. Two large bore catheters are placed in the cephalic veins. If the cephalic veins are not available, the jugular vein is used. Fluid resuscitation through the saphenous veins is unlikely to be successful because of the caudal vena caval obstruction.

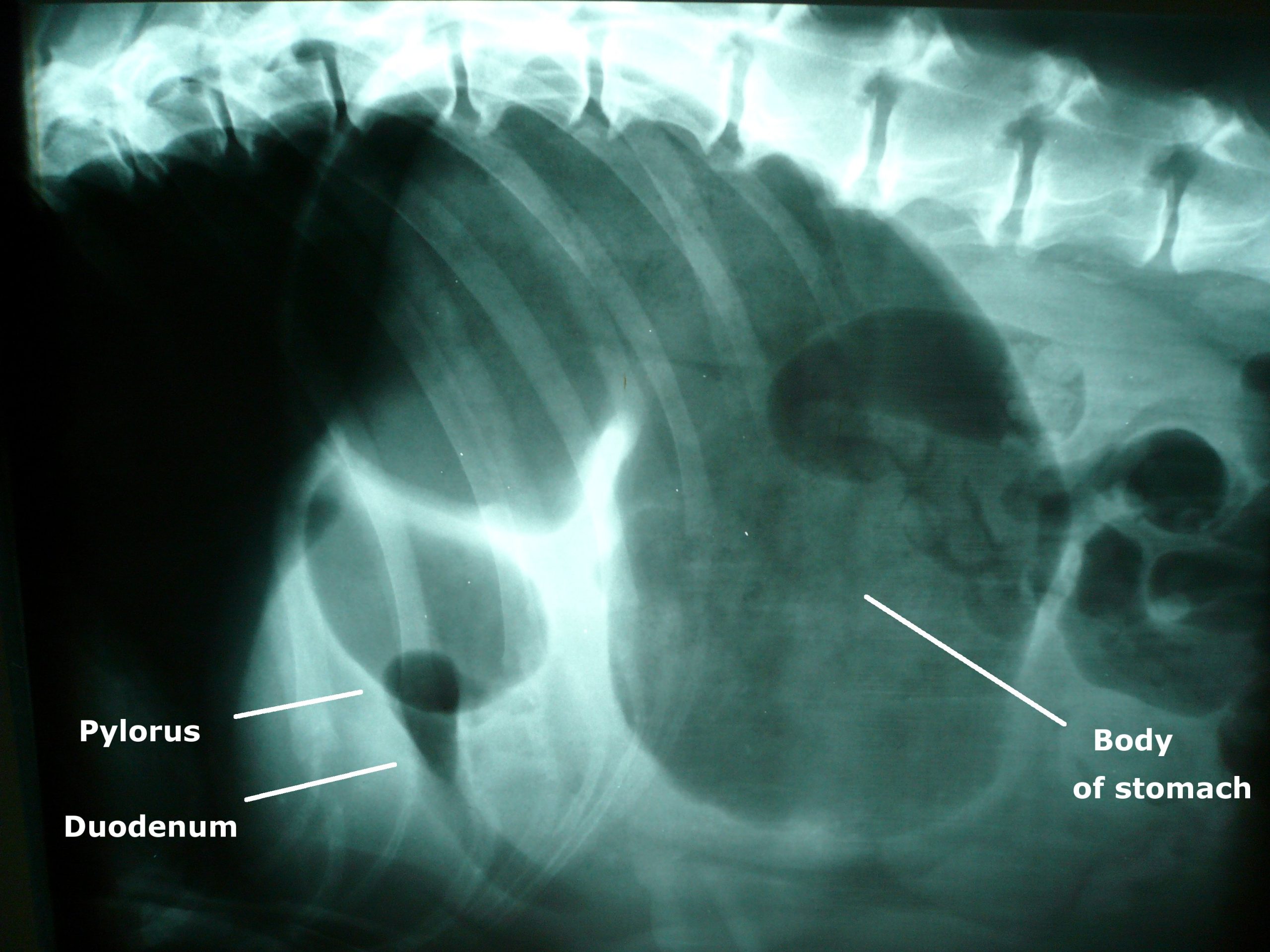

![Photo of an x-ray showing gastric dilatation and volvulus in a large mixed-breed dog. The large dark area is the gas trapped in the stomach. The pylorus and duodenum are in an abnormal position cranial to the stomach and are separated by a fold in the stomach, creating a "double bubble" appearance. By Joel Mills (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.vettimes.co.uk/app/uploads/2013/10/GDV_x-ray-300x225.jpg)

Image by Joel Mills [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons.Either isotonic crystalloids (90ml/kg in the first hour) or hypertonic saline (7% NaCl in 6% Dextran: 5 ml/kg given over five minutes) followed by crystalloid are administered.

Controversial treatments

The use of corticosteroids remains controversial. They have many theoretical benefits but have not been unequivocally demonstrated to improve survival in cases of gastric dilatation-volvulus (GDV).

Prophylactic antibiotics are also somewhat controversial, but rational arguments are made for their use. GDV dogs do have increased levels of circulating endotoxin, perhaps indicating increased GI mucosal permeability. Poor perfusion to the liver could inhibit reticuloendothelial function.

Improving tissue perfusion by fluid resuscitation and subsequent gastric decompression and de-rotation can potentially result in the production of damaging, highly reactive oxygen free radicals. These radicals can cause significant reperfusion injury that may be as damaging as the initial hypoperfusion episode.

It is possible treatment to prevent free radical generation may be beneficial in dogs with GDV. Of the drugs trialled in experimental models, deferoxamine, an iron chelator, shows the most promise for clinical application.

Gastric decompression

Ideally, a continuous electrocardiogram is connected. Once the animal has been stabilised, gastric decompression is attempted using a silicone or rubber tube. The tube is pre-measured to the level of the stomach and marked. A 2in roll of tape is placed in the dog’s mouth and the tube passed through the tape and slowly into the oesophagus and stomach.

If resistance is encountered at the level of the cranial oesophageal sphincter, the tube must not be forced, as this could cause rupture of the caudal oesophagus.

In some fractious animals, sedation and intubation is necessary for gastric decompression. If orogastric intubation is unsuccessful, the stomach is decompressed by trocarization. The abdomen is carefully palpated, and the enlarged spleen is avoided. A large gauge catheter (10-12F) is placed into the stomach percutaneously to relieve pressure.