As regular readers of this blog may have noticed, I was a little apprehensive about starting my final year at veterinary school…

Having already been in the small animal hospital for two days, we finally received our results – confirming I and many of my fellow classmates had passed our exams and could now wear our final year jackets without guilt and walk around the hospital without feeling like imposters.

However, despite now knowing we had qualified to be in the hospital, it still felt like we had been thrown in the deep end.

In at the deep end

My first rotation was emergency and critical care, with the first part being internal medicine. The first couple of days were spent frantically researching the background of patients coming in for appointments, bumbling through clinical exams and brushing up on my rusty practical skills.

It was my first time taking consults alone and, after missing out key questions the first few times, I eventually got into the swing of things and made fewer mistakes.

Despite feeling like I didn’t know anything to begin with, I at least managed to scrape together a few sensible ideas when clinicians tried to worm differentials out of us. It has been a steep learning curve, changing the way of thinking entirely to apply things to a real patient in front of you, which usually has not read the textbook.

OOH my goodness

Just as I was beginning to feel comfortable with medicine, we swapped to out of hours – which, against my presumptions, turned out to be a really enjoyable week.

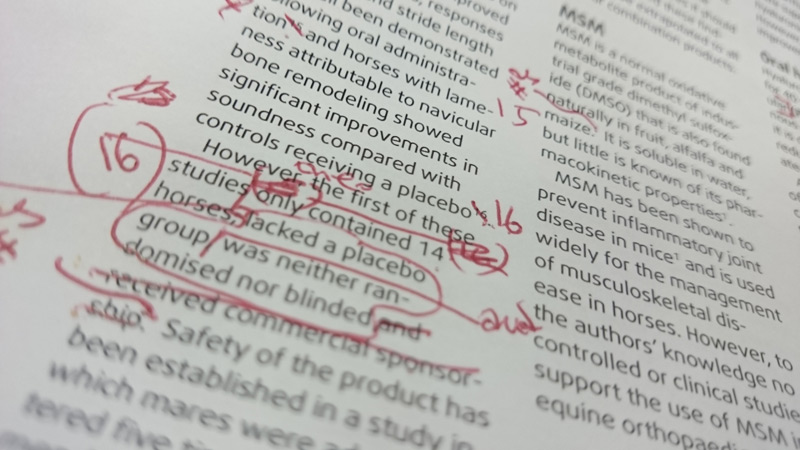

I adjusted to nights far easier than I expected and was powering through until one particularly long night when a bulldog came in with a suspected gastric dilatation volvulus (GDV).

This was the first genuine emergency we’d been involved in and stress levels were running high. Having rapidly set up fluid boluses, taken radiographs to confirm our suspicions, checked lactate levels and run in-house bloods, we went through to theatre. After a very long night of surgery and having warned the owner of an extremely grave prognosis, we were delighted to see said bulldog looking bright and happy the following evening, eating and pulling us down the corridors to the runs outside.

Not all GDVs end with such a happy ending, as we had learned earlier in the week – a dog that underwent the surgery at its own vets came to us for overnight care in ICU and, after a rocky night of a supraventricular tachycardia that we struggled to keep under control, crashed the following morning, was resuscitated successfully once, but could not be saved when it crashed again minutes later.

Hearts, not brains

Coming from nights straight back into days, however, was much harder and I felt like a zombie for the first day of my cardiology week.

On the subsequent days, when my brain was working again, I was able to make a bit more sense of echocardiography and gain a better understanding of some conditions and the tray menu options available.

I also learned a bit more about the genetics of Bengal cats and found trying to heart scan a cat that’s only two generations away from a leopard cat can be quite challenging (and may involve chasing said cat around the ultrasound room for some time, following an artful escape act).

This year isn’t going to be a picnic, but, although I already feel exhausted, if last month is anything to go by, it will be an enjoyable one.