In a world currently filled with sacrifice and compromise, the cancellation of a week’s EMS over the Easter holidays did not, at first glance, seem like a hardship.

Of course I had been looking forward to my first ever farm-practice placement – especially as only a week or so before I had tried my hand at my very first rectal exam and even understood, with sudden and unexpected glee, what some of those lumps and bumps actually were.

But the idea of a little extra time with the family and a whole additional week to focus on upcoming exams meant that, initially, I was not too disheartened.

What does it mean?

Now we’re several weeks deep into lockdown, with no clear end date on the calendar and firm Government advice to “not expect a return to normality anytime soon”, what does this mean for my friends, colleagues and peers at veterinary school – my unlucky year in particular? The situation is different for each year.

First-year students

Poor freshers have had to miss out on Easter lambing season – an unspoken rite of passage into the vet student community. After all, if you’ve never come home without bodily fluids in your hair, are you really one of us?

Second-year students

Second years are having to postpone pre-clinical EMS, compared to those in their fourth year who are sacrificing what could be termed “the good stuff” – that is, real problems in real practices, suturing, injecting, slicing, dicing and all of that (though maybe not the last one). But hopefully the majority of these students will have managed to gain experience in their respective levels of training over the summer of 2019.

Final-year students

Final years have been somewhat of a priority, and rightly so, with special arrangements being made to ensure they graduate fully qualified and at no more of a disadvantage than those who graduated the year before.

My friends and I

Enter now the third years – the year I myself am a part of.

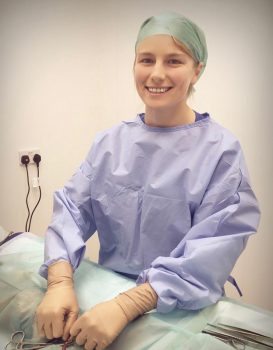

This year marks a transition for us; a stepping stone from sweeping dung from a variety of sources and essentially stepping back to watch the magic happen, to actually doing the magic – or at least attempting it with a sweaty brow under the watchful eye of several veteran professionals.

It’s a big thing. A big, scary, daunting prospect of a thing, but a thing nonetheless – and, given the uncertainty we’re facing in terms of what the future holds for anything and everything, the question is being opened as to what this means for the next generation of vets.

Abnormal

We’ve been told by many officials not to expect “normality” for some time.

“Normality” in this case meaning “the way we’ve always done things” – crowding together in coffee shops, restaurants, and hospital and practice waiting rooms without a care in the world.

“Virus? What virus?” we would say.

But, although certain establishments can change the way they operate – cafés can upregulate hygiene and waiting rooms can impose distancing restrictions – EMS is another matter entirely.

Impractical

Veterinary practices and animal hospitals are undoubtedly some of the cleanest places in the world – because they have to be – and vets themselves are no strangers to singing Happy Birthday twice before eating their lunch. But opening their doors to one or several new vet students each and every week in the coming months might just not be feasibly possible.

A lot of practices – especially independents – are small compared to their human counterparts, which has never really been a problem for us because, luckily, a lot of animals are also rather small. It does mean, however, that, a lot of the time, the two-metre rule just wouldn’t be practical – even if your only purpose is to stand and observe.

For those still needing to undertake pre-clinical placements, a whole new set of challenges exist, including the willingness of farmers to take on students whose help would not be essential, as viral exposure for them could mean a complete loss of livelihood.

Preclinical conundrum

It is an RCVS requirement for all students to complete a minimum of 12 weeks’ preclinical and 26 weeks’ clinical EMS. However, fourth-year students have already had their mandated clinical minimum halved to a mere 12 weeks.

While other years are currently expected to be able to “make up” any missed placements before graduation, the fact the situation is constantly in flux means the RCVS has admitted further reductions may be needed.

While this would certainly be helpful and take some of the pressure off for those of whom meeting the usual requirements would be an impossible feat, one has to worry how this will affect student confidence in the long run.

Key experiences

There is a reason the RCVS has always asked for a certain amount of EMS, and while the number seems daunting at first, it’s only during (or perhaps after) each placement that you can truly see its value.

Practice makes perfect – but, more than that, it builds confidence. It provides an environment in which mistakes are not life-threatening and are safe to be learned from.

With the loss of these key experiences that have helped shape generation after generation of vet students, it is perhaps inevitable that vet schools will have to adapt even further than they already have to limit the knock-on impact of a scenario we have never had to face before.

The RCVS clearly states vets are not legally allowed to prescribe pharmaceutical products for people, but they have no specific guidelines on wound treatment.

The RCVS clearly states vets are not legally allowed to prescribe pharmaceutical products for people, but they have no specific guidelines on wound treatment.