Pancreatitis is one of the most common exocrine conditions seen in small animal practice. It is caused by premature activation of enzymes (zymogens) within the pancreas leading to autodigestion, and can result in severe morbidity with the potential to lead to mortality.

To this day, the diagnosis of pancreatitis remains a challenge – especially in feline patients – and relies on the use of a combination of history, signalment, clinical signs and diagnostic findings.

Presenting signs

In dogs, overweight middle aged to older (more than five years old) are at higher risk. Miniature schnauzers, Yorkshire terriers and silky terriers are some breeds identified as higher risk. Approximately 90% present with anorexia and vomiting, 50% with abdominal pain and 30% with diarrhoea.

In cats, no common age range exists, although domestic shorthair and longhair cats are the most commonly affected. They present more commonly with anorexia and lethargy; 30% presenting with vomiting and 25% with abdominal pain.

Diagnostic changes

A summary of the commonly seen diagnostic changes are included below, many of which due to the nature of the disease are non-specific:

- Hyperlipaemia and an inflammatory leukogram can be present, but are both non-specific.

- Hyperlipasaemia and hyperamylasaemia are commonly seen, but the sensitivity and specificity of both are only about 50%.

- Elevation in alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin can indicate pancreatic bile obstruction. Other changes may be present and can indicate wider organ system involvement – azotemia, for example.

- Canine pancreatic specific lipase immunoreactivity (cPLI) has a high sensitivity, but poor specificity – approximately 50%. This means, if real pancreatitis is present, it will show positive; but a positive result will only actually be real pancreatitis 50% of the time. A negative result, however, can be interpreted as “highly unlikely for pancreatitis to be present”. A positive cPLI should be confirmed with ultrasound, which is the gold standard for canine pancreatitis.

- Feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity (fPLI) has been reported to have a sensitivity of 67% and specificity at 91%. This means, 90% of the time, a positive indicates real pancreatitis – but these figures vary between studies. To make things even more difficult, cats with pancreatitis can have normal fPLI/spec fPL and normal ultrasonographic findings.

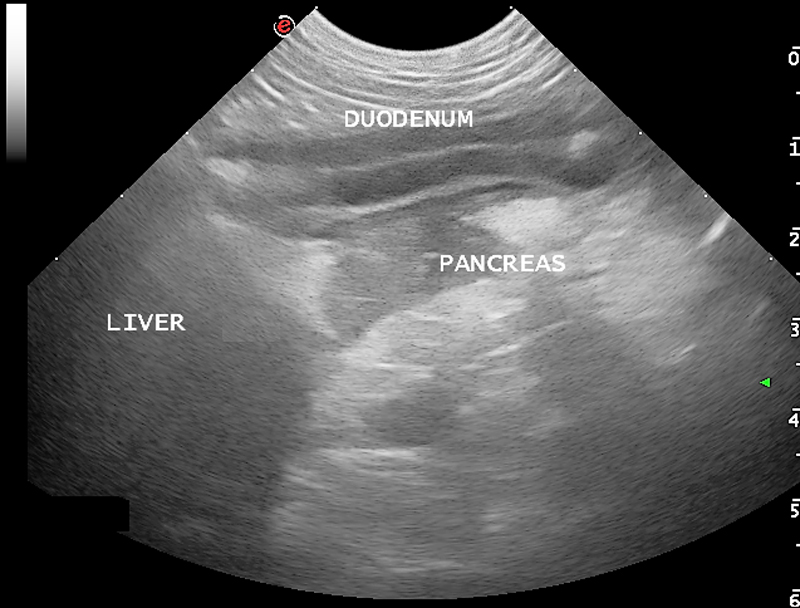

- Common changes on ultrasound with acute pancreatitis include free abdominal fluid (generally a non-septic exudate) and hypoechoic pancreas surrounded by hyperechoic peripancreatic fat. As mentioned above, feline pancreatitis often has no visible changes.

- Radiography may show reduced serosal detail around the pancreatic regions – again, this is not specific or sensitive, but is helpful at ruling out other differentials, such as foreign bodies.

Summary

In summary, canine pancreatitis is less of a diagnostic challenge compared to its feline counterpart. There is no single test that can accurately confirm the presence of feline pancreatitis, apart from in biopsies via exploratory laparotomy – which are understandably invasive and costly.

Next week, we will cover the fundaments of managing pancreatitis patients.

The process is quick – 10 to 20 seconds

The process is quick – 10 to 20 seconds