Christmas is a great time for family gatherings, but this does not necessarily mean it is a great time for pets.

In fact, it can often be the opposite, with veterinary clinics seeing a major increase in patient numbers that come through the door.

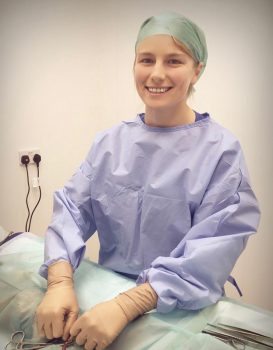

One common emergency we see at the emergency hospital during the festive season is dog fight and bite wounds. As vets, we have a duty of care to educate pet owners during this time, so they – and their pet – have the best Christmas possible and do not end up in the emergency room.

Why do dogs fight and bite at Christmas?

Usually during the festive period, family or friends increasingly gather to celebrate. Whether it is people coming into their home, or them being taken to someone’s home, this can be confusing and cause anxiety levels to rise.

When a family member or friend brings a new pet into the house with an existing pet, it creates competition for food, space, affection and attention – and this can lead to dog fights. Even usually mild-mannered pets can easily feel threatened by a new pet entering their territory, and may lash out.

Increases in noise, people, decorations and general chaos during the holiday season can cause stress and anxiety. For dogs protective of their domain and the people in it, this can be a difficult and uncertain time.

Children not used to pets, and pets not used to young children, can also be a dangerous combination. Dog bites are a common injury sustained by children during the festive period and it could often be avoided.

Solutions

Although dogs are part of the family, it is important owners understand leaving their dog at home when they go to a festive gathering is not leaving them out, but protecting them and making sure they are more safe, comfortable and happy.

If hosting a party, owners can shut their dog in another room away from the chaos and noise – they will be grateful to have a peaceful space. This is a must for a dog already prone to stress.

Children and dogs should not be left alone and should be monitored at all times. If the dog starts to show signs of anxiety and stress, it should be taken somewhere it feels comfortable and calm.

Owners can take their dog to their vet for a behavior assessment. Anti-anxiety medications could be considered in extreme cases, but this would be a last resort.

Communicating messages

We can educate pet owners in the lead-up to Christmas in many ways. We can offer thoughtful, engaging and informative advice and guidance.

Some ways to communicate festive dangers to pet owners include:

- infographics

- videos

- social media posts

- posters in the hospital or clinic

- blogs

- email campaigns

- discussing the dangers at check-ups and appointments

- newsletters

- flyers

- special calls to clients with an anxious pet

- education events, such as how to manage pets and children

Here’s to a very merry – and safe – Christmas.

The RCVS clearly states vets are not legally allowed to prescribe pharmaceutical products for people, but they have no specific guidelines on wound treatment.

The RCVS clearly states vets are not legally allowed to prescribe pharmaceutical products for people, but they have no specific guidelines on wound treatment.