Idiopathic acute haemorrhagic diarrhoea syndrome (AHDS) – previously known as haemorrhagic gastroenteritis – remains the one disease where constant debate exists as to whether antibiotics should be used as part of the standard treatment.

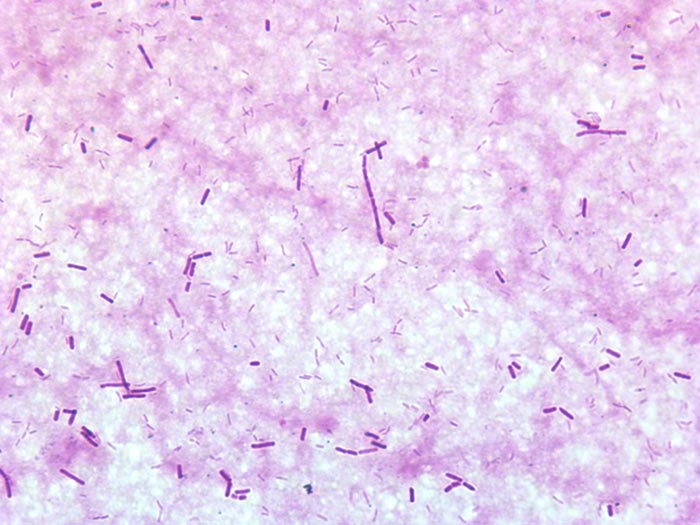

The logic behind using antibiotics to prevent bacterial translocation is sound, and if AHDS is truly initiated by Clostridium species or their toxins then the use of antibiotics can be justified.

However, no knowledge exists of the true frequency of bacterial translocation in AHDS patients and conflicting evidence supports Clostridium being the initiating cause of AHDS in dogs.

Together with new data indicating the use of antibiotic therapy in aseptic AHDS patients did not change the case outcome or time to recovery, the benefit of using antibiotics must be weighed against the very real risk of selection of antibiotic resistance and other complications associated with inappropriate antibiotic use.

In this blog, we will explore the evidence against the use of antibiotics in AHDS.

Cause unknown

AHDS is characterised by an acute onset of vomiting (of less than three days’ duration) that can quickly progress to haemetamesis, and severe and malodorous haemorrhagic diarrhoea, accompanied by marked haemoconcentration that can be fatal if left untreated.

AHDS is a diagnosis of exclusion; other diseases (such as canine parvoviral enteritis, thrombocytopenia, hypoadrenocorticism, azotaemia, hepatopathy, neoplasia, intussusception, intestinal foreign body and intestinal parasitism) must be ruled out by a combination of medical history, vaccination status, complete blood count, serum biochemistry, coagulation times, diagnostic imaging and faecal testing.

Small breed dogs – in particular, the Yorkshire terrier, miniature pinscher, miniature schnauzer and Maltese – have been found to be particularly predisposed. On average, the affected dogs were young (a median of five years old).

The cause of AHDS is still unknown. Clostridium perfringens and its toxin has been incriminated as being the initiating cause; however, conflicting studies have refuted this claim. It is also difficult to determine whether overgrowth of Clostridium species is primary or secondary to the intestinal injury.

Virus theory

Another theory is viruses may have a role in AHDS’ aetiology. At this stage, only single agents had been investigated. It is possible a novel agent not yet been tested is the cause of this syndrome, or possibly the syndrome is the result of a very complex interaction between multiple organisms or their toxins.

For the aforementioned reason, no indication exists for the use of antibiotics to treat for the underlying cause.

Another argument behind the use of antibiotics lies in the fact most idiopathic AHDS patients have several risk factors for bacteraemia.

Necrosis of intestinal mucosa, leading to the disruption of the gastrointestinal mucosa-blood barrier; adherence of significant numbers of bacteria to the necrotic mucosal surfaces that increases the risk of bacterial translocation; significant hypoalbuminaemia indicating substantial loss of mucosal epithelial layer; splanchnic and intestinal hypoperfusion, leading to reduced intestinal barrier function; and microbial dysbiosis all contribute to an increased risk of bacterial translocation.

Although bacterial translocation has the potential to lead to sepsis, the true incidence of bacterial translocation needs to be established in idiopathic AHDS patients, as well as their influence on the outcome of the patients.

Antibiotic requirement

Multiple studies have suggested antibiotics are not required in the treatment of aseptic idiopathic AHDS patients.

In a prospective study of bacteraemia in AHDS dogs by Unterer et al (2015), the incidence of bacteraemia of patients with idiopathic AHDS was 11%, compared to those of healthy controls, where it was 14%.

Transient bacterial translocation to mesenteric lymph nodes occurred in 52% of dogs undergoing elective ovariohysterectomy (Dahlinger et al, 1997), and confirmed in studies by others (Harari et al, 1993; Howe et al, 1999; Winkler et al, 2003), where portal and systemic bacteraemia was reported in clinically normal dogs.

As long as the immune system is competent, and the functional capacity of the hepatic reticuloendothelial system is not overwhelmed, the body is usually effective at eliminating organisms from the blood.

This is reflected in the Unterer et al (2015) study result, where – regardless of the bacteraemia status – all idiopathic AHDS dogs survived to discharge.

In another prospective, placebo-controlled, blind study by Unterer et al (2011), idiopathic AHDS patients were either treated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for six days or a placebo, and no significant difference occurred between the treatment groups concerning mortality rate, duration of hospitalisation or severity of clinical signs.

They concluded, without the evidence of sepsis, antibiotics do not appear to change the case outcome or shorten the time to recovery.

Negative impacts

The negative impacts of inappropriate antibiotic use are undeniable – especially in a time where resistance has become a worldwide public health concern.

Use of unnecessary antibiotics not only disrupts the protective mechanisms of a normal intestinal microflora, but also the real risk of post-antibiotic salmonellosis and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea.

With evidence all pointing against the use of antibiotics as routine treatment of aseptic idiopathic AHDS, next time you are about to reach for antibiotics, I urge you to reconsider. Although it has taken some time to adopt and requires clear communication with clients, all vets should feel comfortable not using antibiotics for AHDS patients.