In patients with respiratory compromise, it is important to look at the respiratory components of the blood gas to determine both oxygenation ability and adequacy of ventilation.

To assess oxygenation, the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) to fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) ratio, and alveolar-arterial gradient (A-a gradient) can be used. Conversely, the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) is what dictates the adequacy of ventilation.

Before going further, it should be noted only arterial samples can be used to evaluate oxygenation. Peripheral venous blood samples are rarely useful for oxygenation assessments, as the values are highly influenced by local factors and the degree of occlusion of the vessel from which the sample was collected from.

Ventilation, conversely, can be assessed from either venous or arterial samples. The PCO2 values from the arterial samples are usually about 5mmHg to 10mmHg lower than the corresponding venous sample.

Abnormalities

Oxygenation and ventilation are not interchangeable terms. Adequate ventilation does not necessarily equate to adequate oxygenation, and vice versa.

Oxygenation is determined by efficiency of oxygen absorption into the blood stream, after passing through the lungs, then delivered to the tissue. It is dependent on both ventilation (V) and perfusion (Q).

For proper oxygenation to occur, matching ventilation and perfusion must occur at the level of the alveoli. When a V/Q mismatch occurs, blood is not properly oxygenated after passing through the lungs, referred to as venous admixture.

Three forms of V/Q abnormalities exist:

- Low V/Q can be caused by:

- pneumonia

- asthma

- pulmonary oedema

- inflammation

- pulmonary thromboembolism

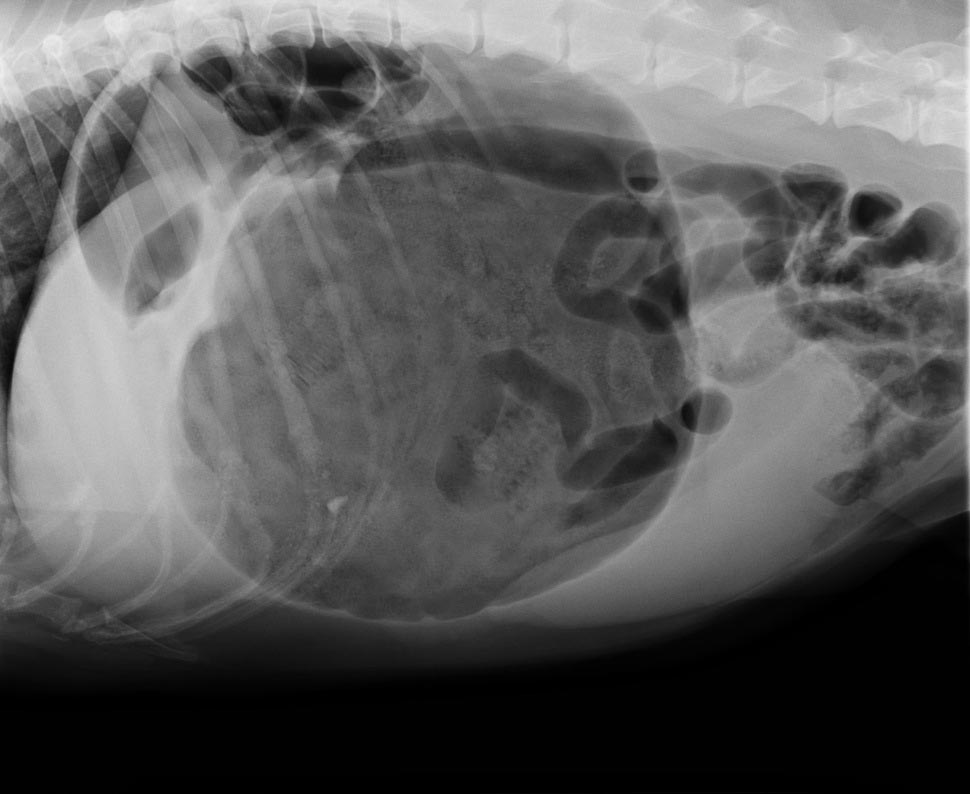

- pulmonary neoplasia

- Absent V/Q means blood has been diverted from parts of the lungs that are inadequately ventilated, such as those caused by atelectasis and alveolar collapse secondary to severe pleural effusion.

- Diffusion impairment is caused by an increased distance between the gas exchange surfaces and pulmonary arterioles (rare in small animals). Pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are among some of these causes where it can be severe enough to cause V/Q mismatch and, therefore, decreased PaO2.

PaO2 to FiO2 ratio

One way to determine the adequacy of oxygenation is by looking at the PaO2 to FiO2 ratio.

FiO2 represents the percentage of the oxygen the patient is breathing. Room air is 21% oxygen, so the FiO2 is 0.21. PaO2 is normally about five times that of FiO2; therefore, the normal PaO2 of a patient with no pulmonary disease breathing room air should be about 100mmHg (5 × 21%).

A normal PaO2 to FiO2 ratio is between 300 and 500. A number lower than 200 implies significant pulmonary disease or, possibly, acute respiratory distress syndrome. This ratio is particularly important in assessing patients requiring supplemental oxygen. An example is a congestive heart failure patient on bilateral nasal oxygen line (approximately FiO2 of 40%), with a PaO2 value of 80mmHg. The PaO2 appears to be adequate until the ratio is calculated (80/0.4 = 200). The change in FiO2 ratio is often more important than the PaO2 as a lone value.

A-a gradient

Once hypoxia has been established, the A-a gradient will help determine whether it is caused by ventilation failure or an underlying pulmonary disease. “A” stands for alveoli and “a” stands for arterial concentration of oxygen.

A = [FiO2 × (Pb-PH20)] – (PaCO2/0.8) – Pb is the barometric pressure (760mmHg at sea level), and PH20 is saturated water vapour pressure, which is 50. The 0.8 is the respiratory quotient and affixed number.

The simplified formula assumes the patients are breathing room air (FiO2 of 0.21) and at sea level, and the formula can be simplified to: A = 150 – (PaCO2/0.8)

A normal A-a gradient should be less than 15. Abnormally high values indicate pulmonary parenchymal disease or an underlying heart disease, while a normal A-a gradient indicates the cause of hypoxia is likely secondary to ventilation failure.

The ‘120 rule’

Ventilation is particularly important to assess in animals with respiratory compromise, as it represents the entire mechanics of breathing.

PCO2 is not only representative of the efficiency of ventilation, but also cellular metabolism and perfusion. Low PCO2, or hyperventilation, is rarely of any significance as aforementioned in the respiratory alkalosis section. High PCO2, however, is indicative of the lungs’ reduced ability to adequately shift air and can be caused by neurologic diseases, spinal cord injury, upper airway disease, trauma to the thoracic wall or muscles, and drugs that can cause respiratory depression.

Ventilation must be assessed in light of oxygenation, as both are often affected by each other. An example of this would be a hypoxic animal (low PaO2) with a compensatory hyperventilation (low PCO2). The “120 rule” will help determine whether lung function is adequate.

If the value you get, by adding the PaO2 and PaCO2, is greater or equal to 120, lung function is adequate. If the value is lower than or equal to 120, lung function is abnormal. This can only be calculated from patients breathing room air and at sea level.

Ventilation adequacy

Aside from looking at values on a blood gas, it is equally important to monitor the patient to determine whether the ventilation effort is sustainable.

Animals with a significantly increased respiratory effort – despite normal blood gas values – are at risk of respiratory exhaustion and indicative of mechanical ventilation intervention.

From these respiratory components of the blood gas value, clinicians should be able to determine the adequacy of ventilation, whether hypoxia is present and, if it is, whether the underlying cause is a result of ventilation failure or a possible underlying pulmonary or heart disease.

Once oxygen supplementation has been implanted, the PaO2 to FiO2 ratio will help clinicians decide whether the response is adequate or mechanical ventilation is required.

As with all laboratory measurements, it is extremely important to assess the patient itself. Non-sustainable respiratory efforts, in the face of normal blood gas parameters, is still an indication for mechanical ventilation.