The previous post wrapped up with tips to help you build confidence, keeping in mind that we’re not focusing on confidence just for our own sake – we’re using confidence as a building block towards building trust with our clients.

Remember, why would your clients trust you if you don’t trust yourself?

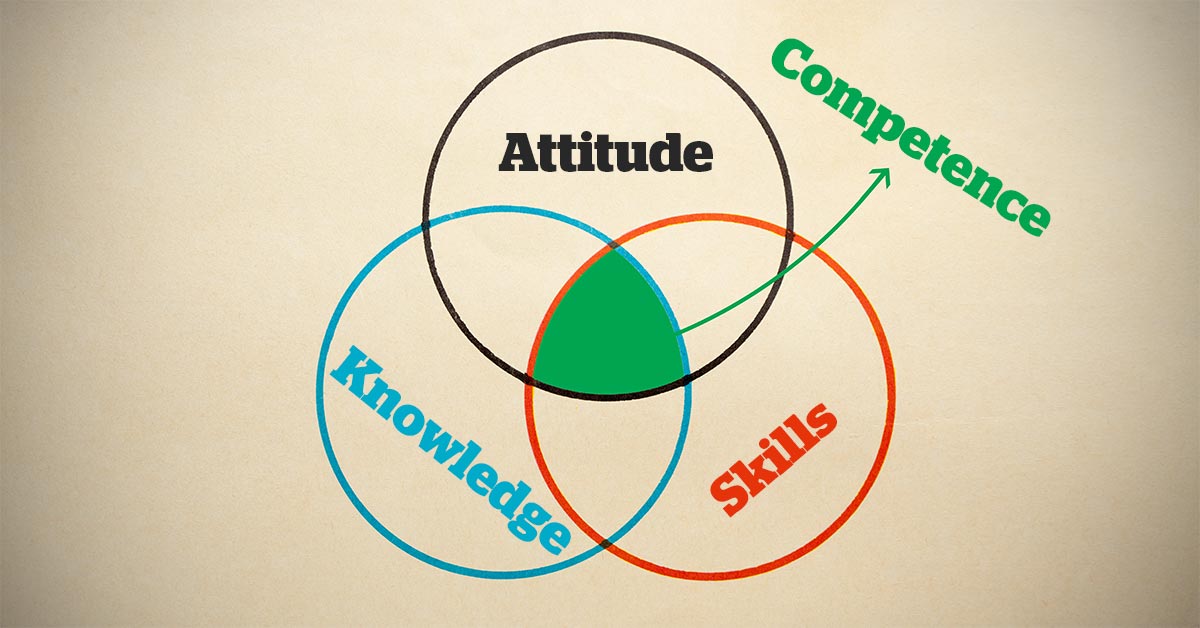

The next trust-building tool is Competence. If you want someone to trust you with his or her pet, he or she needs to know that you know what you’re doing, right?

But more exists to competence than simply showing that you know your stuff – it’s also about knowing that you know your stuff, which, of course, leads back to last week’s topic of confidence.

Competence breeds confidence, which will make it easier for you to try new things and learn new skills, which, in turn, will lead to even more competence. More feedback loops…

Here are some practical ways to use competence as a tool for perfect consults.

Show competence

Your clients want to know you are good at your job before fully trusting you.

The problem is, they don’t get to see you shine once you leave the consult room, so you need to make sure you demonstrate competence in your dealings with them.

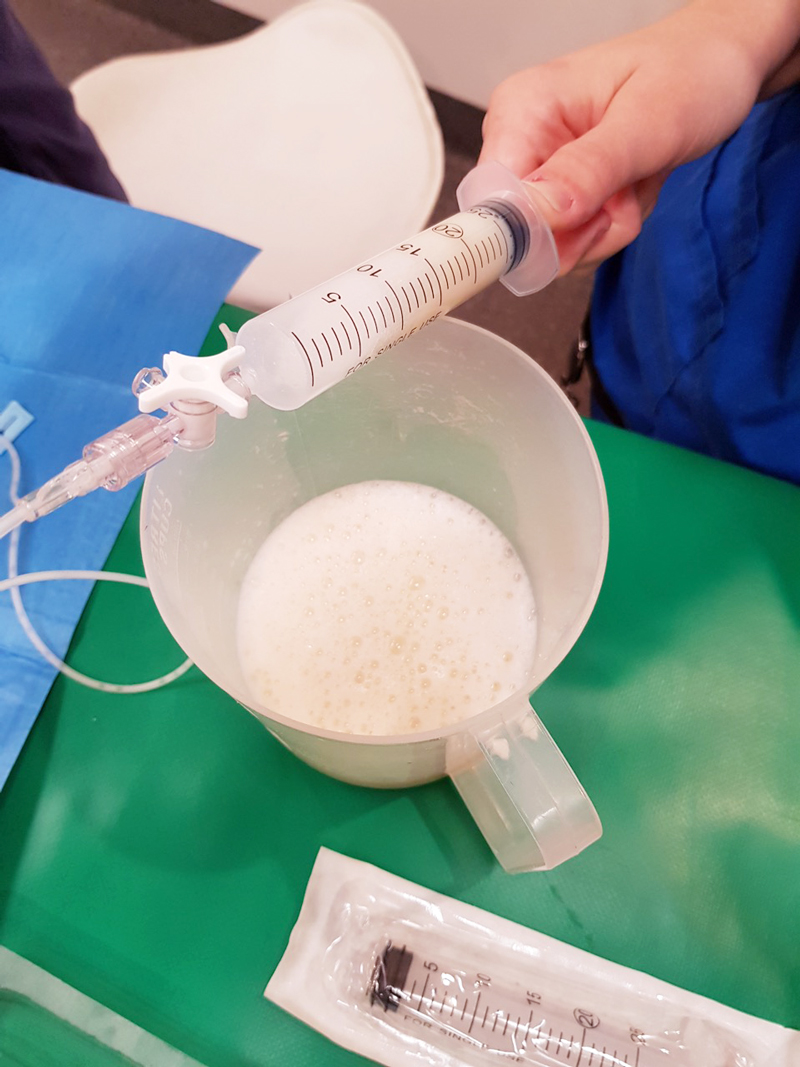

This means making sure you know how the practice software works, know the vaccination protocols, how to confidently examine their pet, how to give an injection… the basics we mostly take for granted.

If you appear to be a bumbling buffoon with the simple things, clients will presume you’ll be the same where it really matters.

Talk about how competent you are

Don’t be afraid to talk yourself up a bit. You can sell yourself – whether it’s your own skills, or your clinic’s – without being arrogant. For example:

- “I have a special interest in skin cases, so I’m confident we can make a big difference here.”

- “We see a lot of these cases, and we have high success rates.”

- “Dr X, who will be doing the surgery, is one of the best in the business.”

Develop competence

It’s much easier to feel like your good at something when you are actually good at something.

Resist the default of the aimless drift towards mediocrity – “Jack of all trades, but master of none.” Pick something – anything – and spend a bit of time polishing your skills in it. The manky ear, in-house cytology, behaviour, treating seizures, reading radiographs, dealing with angry clients, fixing canaries… anything.

Distinguish yourself by becoming a “mini-specialist” in something, so that the next time one of those situations arises you absolutely smash it.

Others will see this. Your clients will see it. People will acknowledge your skill and, maybe, praise you. Someone less skilled may start deferring to you the next time they have a similar case.

These things will light up all those feel-good social centres that our minds have evolved for, which will give you a massive confidence boost. Which, as we just said… have I mentioned feedback loops?

- The next part look at the final C needed to establish trust with your clients.

![Cytology of a mast cell tumor from a Labrador retriever at a magnification of 1,000x. By Joel Mills (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.](http://www.vettimes.co.uk/app/uploads/2014/06/Mast_cell_tumor_cytology_2-300x284.jpg)