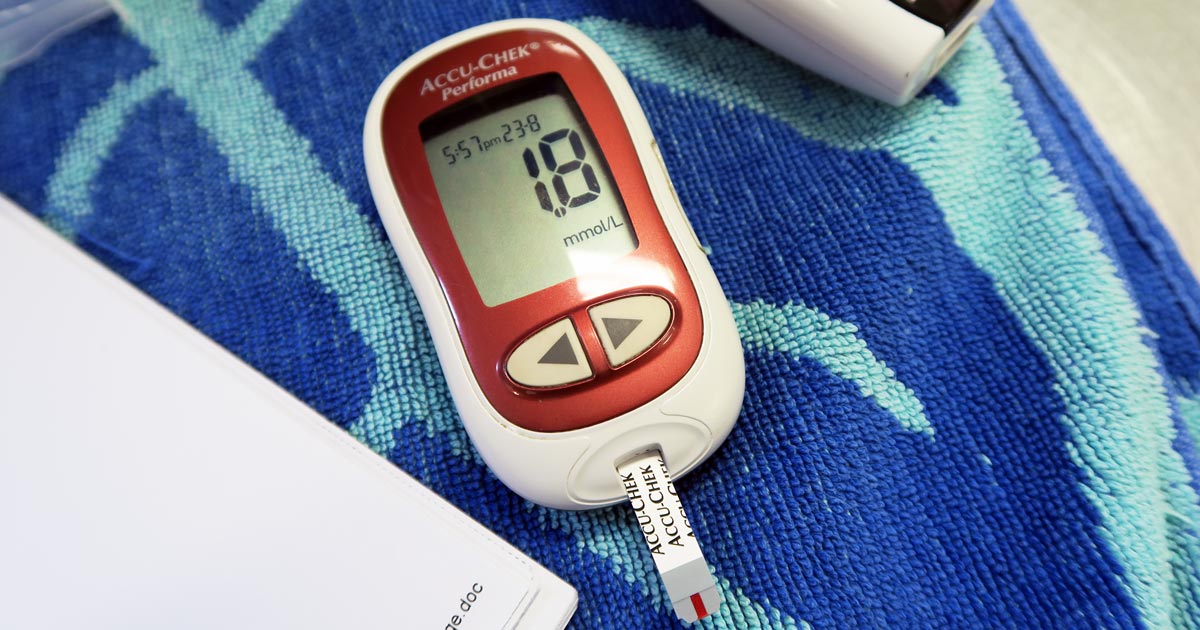

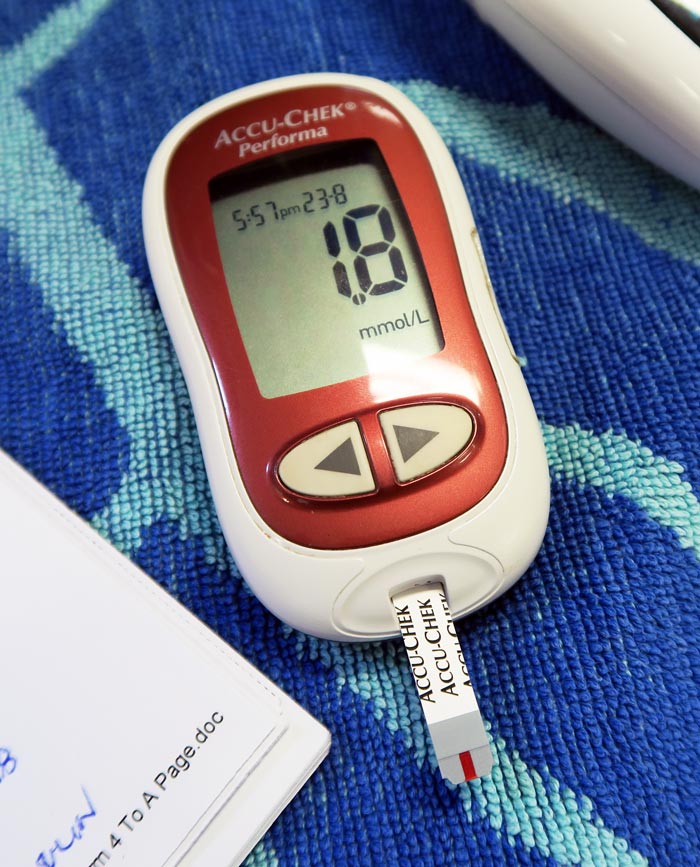

Blood glucose is an important parameter that should be included in every “emergency database”.

Hypoglycaemia is considered when blood glucose levels drop below 3.5mmol/L or 63mg/dL. Symptoms can start as being vague, such as lethargy and weakness, then progress to tremoring and seizures.

One important point is that, in an emergency setting, although reduced food intake or starvation is written in text books, unless the patient is very young or a very small size it is not a common cause of hypoglycaemia.

The liver has a fairly substantial capacity to continue to produce glucose during periods of reduced eating or starvation.

Common causes

The common causes of hypoglycaemia I see in an emergency setting are:

- sepsis: bacteria consumes glucose

- hypoadrenocorticism: lack of cortisol

- insulin overdose: excessive intracellular shift

- insulinoma: malignant insulin secreting neoplasia of the pancreas

- hepatic insufficiency: reduce production

Treatment is fairly straightforward and the impact is often dramatic – 0.5ml/kg to 1ml/kg of 50% dextrose diluted 50:50 with saline given slow IV over a couple minutes (to reduce the risk of haemolysis).

As the list of possible causes shows, a one-off dose of glucose is often not enough.

Glucose supplementation often needs to be continued as a 2.5% continuous rate infusion (CRI), with frequent blood glucose monitoring and adjustments made to the rate as necessary.

The CRI will need to be continued, as the hypoglycaemia will often continue to occur until the primary disease process is identified and appropriately addressed.

Emergency database

It is not uncommon to read or hear the term emergency database. This contains a number of blood parameters performed, which include:

- blood glucose

- alanine aminotransferase

- lactate

- blood urea nitrogen

- PCV

- total protein or total solids

- activated clotting time

- acid-base balance

- electrolytes