January brings with it an onslaught of well-intentioned gym memberships, diets and resolutions that often get forgotten fairly rapidly.

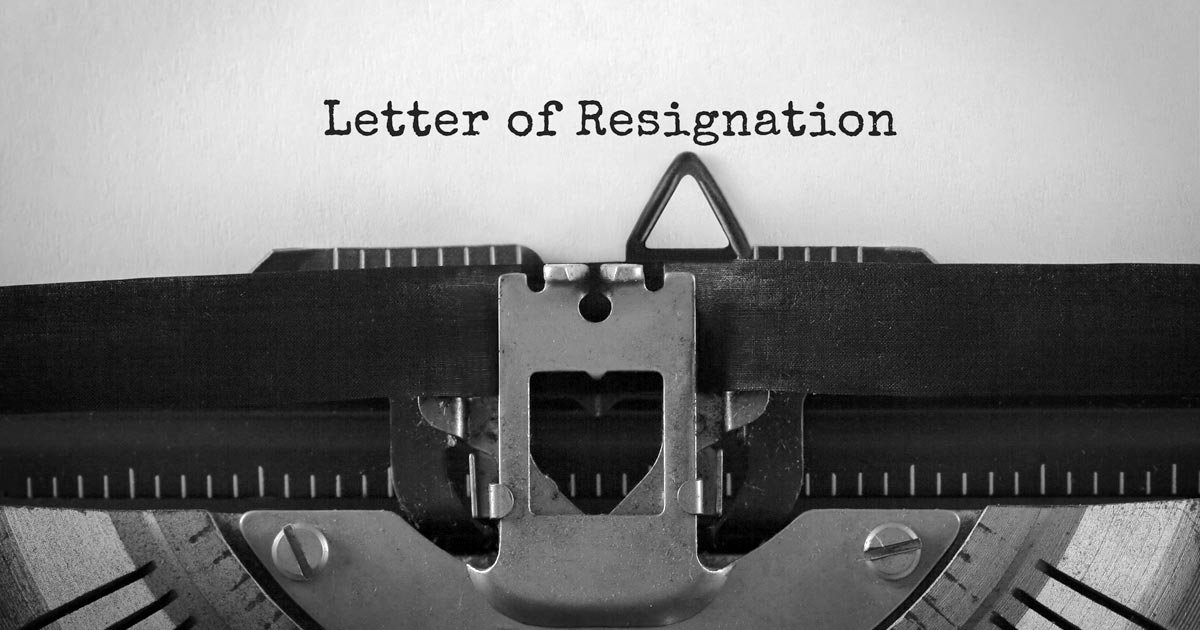

For me, my “happy new year” was tainted with uncertainty, as I had made the scary decision to leave my first job as a new graduate vet – quite literally forcing the “new year, new start” cliché on myself.

This decision was not made lightly. In fact, if I had listened to my gut feeling that things weren’t right, I probably would have left much earlier, but I stuck it out for five months. I had to be sensible – I had rent to pay. But, similarly, I was not going to stay any longer at the cost of my sanity.

Time to take action

Many of my new graduate friends also struggled at their respective workplaces to begin with, so I couldn’t help but think maybe it was just supposed to be hard. But as they all settled, and I seemed to just get more wound up with my situation, I began to accept it wasn’t right.

So, what were my options?

Address my employment concerns

Despite being advertised as a truly mixed practice, I found myself working as a TB tester virtually every day, which became unrewarding and a huge hindrance to my personal development as a vet.

I tried to address the situation, but was met with non-committal responses, such as: “Well, we are very busy with TB at the minute.” No offers of sharing it out were made, considering myself and another new graduate were carrying out all the testing. In fact, I ended up organising the whole practice’s TB equipment, paperwork and bookings.

The other issues I had were also met in a similarly non-helpful manner.

Go above the powers that be

One of the (few) advantages of working for a corporate group is you can go above the powers that be.

Although this provided a friendly listener on the end of the telephone, it didn’t actually achieve much after helping me explore the options of transferring to another practice within the group. As I was still looking for a mixed role, it came to a dead end pretty swiftly.

Hand in my notice

I was very aware my notice period tripled after I had worked at the practice for six months, so I had the choice of leaving before the six months were up or being stuck for at least nine months.

I did try addressing my employment concerns and going above the powers that be first, but I think I knew all along that, in the end, I was going to leave; it was just a question of when – before or after six months, considering the notice period, and before or after I had found another job?

Choice made for me

In the end, some timely external circumstances forced my decision – my landlord informed me he was selling his house, so I would only have a few months left of the lease anyway.

Once I came to the realisation I needed to leave, I felt relieved. This was ultimately short lived as I then faced the question of what to do afterwards – I even started to consider whether I actually wanted to look for another vet job.

But I didn’t have to look far to find some inspiration – my university friends were very supportive of my decision to leave my practice, but their stories of their own experiences were reassuring. The key was finding the right practice and being able to enjoy being a vet rather than seeing it as the stressful, unfriendly job with long hours it’s often portrayed as.

Negative into a positive

I began the job search slightly before handing my notice in – I think as a safety net, as I was still very apprehensive about being caught out with no work. I was also very concerned about how not having spent very long in my first practice would look to potential employers – would they think I couldn’t hack the pressure and gave up too easily?

My first interview this time around, however, was a massive confidence boost – my worries were ill-placed as my decision to leave my practice was only viewed as a positive move; that I was being proactive in my career development and not putting up with an environment in which I wasn’t progressing.

When more interviews and then job offers started emerging, I found the confidence to not only hand in my notice, but also to turn down offers that weren’t right for me.

Disguised desperation

We regularly hear about the shortage of vets in the veterinary press, on Facebook, through word of mouth and, for those working in understaffed practices, via first-hand experience. But nothing confirmed the veterinary employment crisis more than the poorly-disguised desperation some practices exhibited when I enquired about vacancies.

Yes, I was a little more desirable than a new graduate fresh out of university because I had worked for a few months, but I was still virtually a new graduate. If anything, I felt my skills had regressed since graduation because my confidence had been knocked so severely in my first role.

But I did know how to consult, interact with clients, break bad news, and offer and carry out euthanasia with the client in the room. These are the things you don’t really learn until you qualify; the small things that make a difference between being a startled- looking graduate in your first week being asked “is it your first day?” by a client, and a recent graduate who can give a calm impression of confidence and knowledge (even when you’re a little unsure).

But I did know how to consult, interact with clients, break bad news, and offer and carry out euthanasia with the client in the room. These are the things you don’t really learn until you qualify; the small things that make a difference between being a startled- looking graduate in your first week being asked “is it your first day?” by a client, and a recent graduate who can give a calm impression of confidence and knowledge (even when you’re a little unsure).

It took me a while to convince myself I’d be employable enough to be picky, but with a few offers under my belt, I entered the new year jobless, but knowing so many practices out there were looking for vets.

It did, however, still take a considerable amount of moral fibre to swallow my pride and go to the job centre to sign up for jobseeker’s allowance. This was not without an added push from my ever-knowledgeable other half, who bluntly said: “You’ll be paying into it for the rest of your life, so you may as well claim it while you can.”

Daunting, but rewarding

Although it was daunting to quit one job without having something else lined up, it was the right thing to do and, inevitably, things worked out in the end. With a bit of patience and perseverance, I have now found what I think is the right job.

Although I can’t quite squash the niggling feeling it could all go wrong like the previous one, I like to think I’ve learned something from that disastrous experience, and am feeling much more optimistic.

After much reflection, I think I was just very unfortunate with my first role and a number of factors occurred that I could never have foreseen.

Take advantage

For many people, despite the new year clichés, January becomes a time of reflection. I’m not too sure about “new year, new me” but I’ve certainly ended up with “new year, new job”.

If you aren’t happy in your job, don’t be afraid to take the leap – especially if you’re a new graduate. It is so important your first job is right for you, otherwise it could scar you, and ultimately ruin your entire veterinary career.

It isn’t worth the stress of staying where you are unhappy – so many jobs are out there. It is, as they say, an “employee’s market” at the minute – take advantage of it.

But I did know how to consult, interact with clients, break bad news, and offer and carry out euthanasia with the client in the room. These are the things you don’t really learn until you qualify; the small things that make a difference between being a startled- looking graduate in your first week being asked “is it your first day?” by a client, and a recent graduate who can give a calm impression of confidence and knowledge (even when you’re a little unsure).

But I did know how to consult, interact with clients, break bad news, and offer and carry out euthanasia with the client in the room. These are the things you don’t really learn until you qualify; the small things that make a difference between being a startled- looking graduate in your first week being asked “is it your first day?” by a client, and a recent graduate who can give a calm impression of confidence and knowledge (even when you’re a little unsure).