When the unexpected occurs and patients come through our emergency clinic doors, we will often face times when owners become very difficult to deal with. Understanding where they are coming from may help diffuse the situation, but not unless you have good communication skills.

It’s very a very natural response to become defensive when someone acts aggressively and when you feel threatened, but unfortunately this reaction is counterproductive.

You want to be able to treat their pet and help them, but instead your focus can shift to needing to defend yourself and calm them down.

However, the last thing you want to do is advise your client to “calm down”.

Understand the client

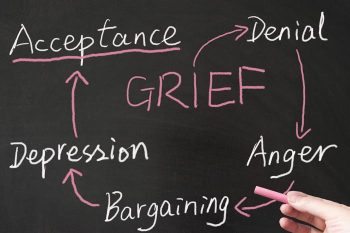

Being able to recognise the five stages of grief can help us understand and deal with the situation more effectively. These are:

- denial

- anger

- bargaining

- depression

- acceptance

Unfortunately, more often than not, it’s nurses and receptionists on the front line who often bear the brunt of this, and it is our job as vets to help them through this process. We need to remind ourselves not to take things personally, as these owners are upset only at the situation and circumstances, not at us.

We need to remain calm at all times and reassure the owners we are here to help them. Owners’ frustration often stems from helplessness and guilt – we all know situations involving much-loved pets can often be driven by anxiety and are highly emotive.

Other times it is because they feel their concerns have not been heard. If you suspect this, you can ask them specifically what they want from us and you’d be surprised how quickly the situation can be resolved once an understanding is reached.

Listen to the client

It is important to listen without judgement or interruption – although we all know that’s easier said than done.

Showing genuine empathy and acknowledging clients’ emotions and concerns can help you quickly build trust with owners. Even if you don’t know all the answers, let them know you are there for the same reason – you both want to help their pet.

As some of you may have experienced, the most emotional owners can often turn out to be some of a vet’s best clients.

Saying that, if you ever feel you are in danger, or that you are unsure of how to handle a situation, always consult with a more experienced colleague or speak with the vet in charge of the case.

It may be advisable to have a practised line of communication, which shows compassion and understanding but removes you from the situation, where you can get additional support or help.

I see every day our veterinary nurses wear their hearts on their sleeves, and difficult clients can sometimes really hurt them. With this in mind, it is important a nurse can have some breathing time and regroup ready for the next client.

We know nurses want nothing more than the best for the pets in their care. Each case will be different, each client will respond differently, so, like we say in emergency, you have to expect the unexpected.

One thing we do know – your veterinarian will never question a nurse’s compassion. When it comes to client communication and pet care, we will always be a team looking out for one another.

The process is quick – 10 to 20 seconds

The process is quick – 10 to 20 seconds