Every vet has their niche, speciality or personal interest. I think I’m slowly finding that mine may be located somewhere in the gastrointestinal (GI) system; as the daughter of an endoscopy nurse I like to think I’m following in the family footsteps.

I was really enjoying my lectures on the topic until we reached the point of hiatal hernias.

The unfortunate cognitive dissonance of veterinary medicine is that the more interesting or objectively “cooler” the case, the more likely it is often incredibly sad from the perspective of the patient.

Vet geek

In this case, I personally was finding the concept of a sliding hernia pretty “cool” (don’t judge, I’ve been out of the game for a year and I’ve missed nerding out over-vetty stuff), until I learned that the majority of brachycephalic dogs suffer from the condition.

The mechanism behind this being that, in an effort to breathe through an actively collapsing airway, a brachycephalic dog can effectively create such a negative pressure that it sucks its stomach through its diaphragm and into its thorax.

The worst part of this is that it’s suspected the majority of cases are subclinical (or, at least, subclinical to the owner), as the main clinical signs associated with nausea, such as drooling and lip smacking, are characteristic of short-nosed breeds anyway.

Less love?

I wonder if a pilot finds it impossible to enjoy a flight? Even if you stuck him in first class with a martini, the Friends box set, comfy slippers and a sirloin steak on the menu, would he be able to switch off, or would he find his mind focusing on minute turbulence? Would he keep checking the altitude, or picturing the cockpit, wondering: “What on Earth is going on up there?”

Along a similar vein, by the time I finish vet school I wonder if I will ever be able to truly enjoy a dog in the way I used to? If somebody had presented me with the fluffiest, most adorably friendly puppy in the world the day before I’d started first year, I’d have been ecstatic – I may even have passed out from happiness.

Not just a puppy

Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m never NOT going to love being handed a puppy, but it’s not just a puppy anymore.

- Has it been vaccinated?

- Was its mother healthy?

- Did the breeder socialise it effectively, or will it forever have a fear of bearded men in funny hats?

- Is there a cleft palate behind those tiny teeth?

- Are there worms lurking in that adorable pot belly?

It’s like my subconscious races to take a history in every animal – even if they’re not a patient!

Natural versus artificial selection

As a constant reminder of my disturbing lecture notes, while tutoring GCSE biology I regularly cover the topic of “natural versus artificial selection” with my students. This includes covering the staggering feet of man’s journey over the past 1,000 years to convert the wolf into anything from a small bear to something that fits in a handbag.

Each time I teach this topic I find myself fighting the urge to be overly pious, knowing no exam will ever ask them to list the ways the pug is destined to a snorting existence or why the dachshund can’t jump onto his owner’s lap for fear of shattering his spine.

I feel including that sort of thing in the syllabus could certainly go a long way – and perhaps the best way to promote healthy dogs is with re-education from the ground up. But is that my responsibility? More importantly, is it the responsibility of vets in general?

Flawed from birth

With some owners (especially breeders), mentioning any predispositions or hereditary conditions of their dog is akin to attacking their personal brand.

Some people are “dog people”, while some are very passionately and unequivocally only “pug people” or “sausage dog people” or “golden people” – and it’s generally a struggle not to cause offense when telling an owner their animal is slightly overweight, let alone that their pride and joy is genetically predisposed to be flawed from birth.

Do better by your pet

The frustrating thing is that if owners knew the risks to their particular pup then prophylactic management could really make a difference to these animals’ lives.

Not walking brachycephalic breeds on hot days, keeping the weight off of larger dogs to take the stress off of their joints – prevention is always better than cure, and if we can’t prevent the breeding and purchasing of puppies with a gene pool so shallow only a gnat could drown in it then at the very least we should be aiming to prevent suffering and promoting comfort.

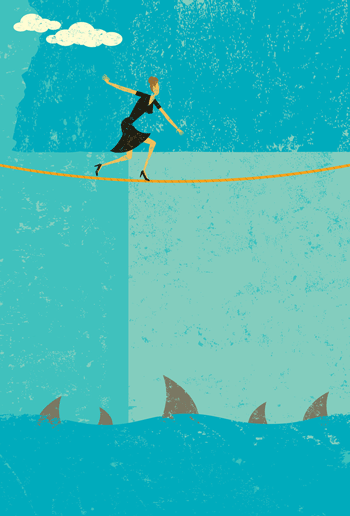

Balancing act

The danger, as always, is that if you tell an owner what they don’t want to hear too many times, they won’t come back. So, the balancing act lies in maintaining the client-vet relationship so as to ensure animal welfare, while not being too pious or condescending.

This is equally important in day-to-day life. Being able to switch off is a must for any professional to maintain mental health, yet it’s sometimes hard to stay quiet when your friend mentions their aspiration to own 50 sausage dogs.

My question for you is, does a vet ever stop being a vet, and is a dog ever really just “a dog”?