Treatment of ionised hypocalcaemia (iHCa) is reserved for patients with supportive clinical signs, then divided into acute and chronic management.

Since the most common cases of clinical hypocalcaemia in canine and feline patients are acute to peracute cases, this blog will focus on the acute treatment and management of hypocalcaemia.

Clinical signs

The severity of clinical signs of iHCa is proportional to the magnitude, as well as the rate of decline in ionised calcium (iCa) concentration.

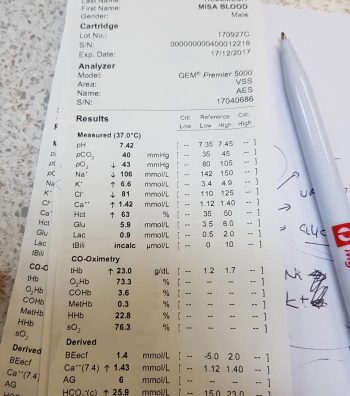

The normal reference range for iCa is 1.2mmol/L to 1.5mmol/L in dogs and 1.1mmol/L to 1.4mmol/L in cats. Serum iCa concentrations in younger dogs and cats are, on average, 0.025mmol/L to 0.1mmol/L higher than adults.

Mild iHCa (0.9mmol/L to 1.1mmol/L) – as seen in critically ill dogs and cats with diabetic ketoacidosis, acute pancreatitis, protein-losing enteropathies, sepsis, trauma, tumour lysis syndrome or urethral obstructions – often has no observable clinical signs.

Moderately (0.8mmol/L to 0.9mmol/L) to severely (lower than 0.8mmol/L) affected animals – in the case of eclampsia and those with parathyroid disease – often display severe signs.

Early signs of iHCa are often non-specific, and include:

- anorexia

- rubbing of the face

- agitation

- restlessness

- hypersensitivity

- stiff and stilted gait

As the serum iCa concentration further decreases, patients often progress to:

- paresthesia

- tachypnoea

- generalised muscle fasciculations

- cramping

- tetany

- seizures

In cats, the gastrointestinal system can also be affected, presenting as anorexia and vomiting.

Treatment

The need for treatment of hypocalcaemia is dependent on the presence of clinical signs, rather than a specific cut-off of serum concentration of iCa itself.

Moderate to severe iHCa should always be treated. Mild hypocalcaemia, on the other hand, may not be necessary, especially if it is well tolerated. It should be remembered the threshold for development of clinical signs is variable, and treatment may benefit critical cases with an iCa concentration of less than 1.0mmol/L.

Treatment is divided into the acute treatment phase and chronic management.

In the tetanic phase, IV calcium is required – 10% calcium gluconate (equivalent to 9.3mg/ml) administered at 0.5ml/kg to 1.5ml/kg dosing to effect. This should be administered slowly with concurrent ECG monitoring. Infusion of calcium needs to be stopped if bradycardia develops or if shortening of the QT interval occurs.

Some suggest calcium gluconate (diluted 1:1 with 0.9% sodium chloride) of half or the full IV dose can be given SC and repeated every six to eight hours until the patient is stable enough to receive oral supplementation. However, be aware calcium salts SC can cause severe necrosis or skin mineralisation.

Calcium chloride should never be given SC, as it is a severe perivascular irritant.

Correcting iCa

Irrespective of the chronicity of the treatment, the rule of thumb is correction of calcium should not exceed 1.1mmol/L.

Correction of iCa to normal or hypercalcaemic concentration should always be avoided, as this will result in the desensitisation of the parathyroid response, predisposing renal mineralisation and formation of urinary calculi.

Some of the more common calcium supplementation medications – both parenteral and oral formulas – are detailed in Table 1. Supplementation of magnesium may also benefit some patients, as it is a common concurrent finding in critically ill patients with iHCa.

| Table 1. Common calcium supplementation medications | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Calcium Content | Dose | Comment |

| Parenteral calcium |

|||

| Calcium gluconate (10% solution) |

9.3mg/ml |

i) slow IV dosing to effect (0.5ml/kg to 1.5ml/kg); acute crisis, 50mg/kg to 150mg/kg over 20 to 30 minutes

ii) 5mg/kg/hr to 15mg/kg/hr IV or 1,000mg/kg/day to 1,500mg/kg/day (or 42mg/kg/hr to 63mg/kg/hr)

|

Stop if bradycardia or shortened QT interval occurs.

Infusion to maintain normal Ca level

SC calcium salts can cause severe skin necrosis/mineralisation.

|

| Calcium chloride (10% solution) |

27.2mg/ml | 5mg/kg/hr to 15mg/kg/hr IV | Do not give SC as severe perivascular irritant |

| Oral calcium |

|||

| Calcium carbonate (many sizes) |

40% tablet | 5mg/kg/day to 15mg/kg/day | |

| Calcium lactate (325mg, 650mg) |

13% tablet | 25mg/kg/day to 50mg/kg/day | |

| Calcium chloride (powder) |

27.2% | 25mg/kg/day to 50mg/kg/day | May cause gastric irritation |

| Calcium gluconate (many sizes) | 10% | 25mg/kg/day to 50mg/kg/day | |

Next time…

The next blog will look at the pathophysiology behind iHCa among critically ill animals. It will also look at the controversy regarding treatment of non-clinical iHCa cases and the prognostic indications of iCa concentrations.