Low ionised calcium (iCa) is a widely recognised electrolyte disturbance in critically ill human patients who have undergone surgery, are septic, have pancreatitis, or have sustained severe trauma or burns.

Similar changes occur in our critical canine and feline patients, though less well documented.

Calcium plays a vital role in a myriad of physiological processes in the body, so any deviation from the very narrowly controlled range is associated with severe repercussions.

Low iCa has many causes; however, this three-part blog will only focus on the more common and peracute to acute causes. It will also discuss the treatment of low iCa and the controversy behind treatment of iCa in critically ill patients.

Forms

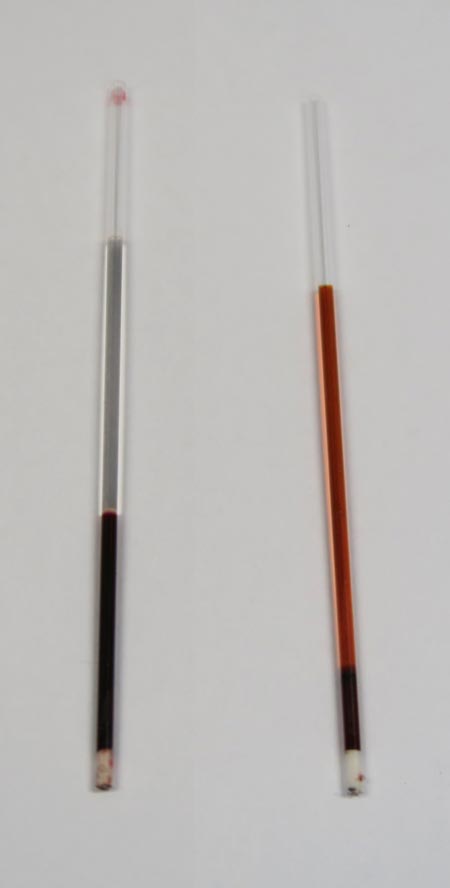

Calcium in the serum or plasma exists in three forms:

- ionised or free calcium

- protein-bound calcium

- complexed or chelated calcium (bound to phosphate, bicarbonate, sulfate, citrate and lactate)

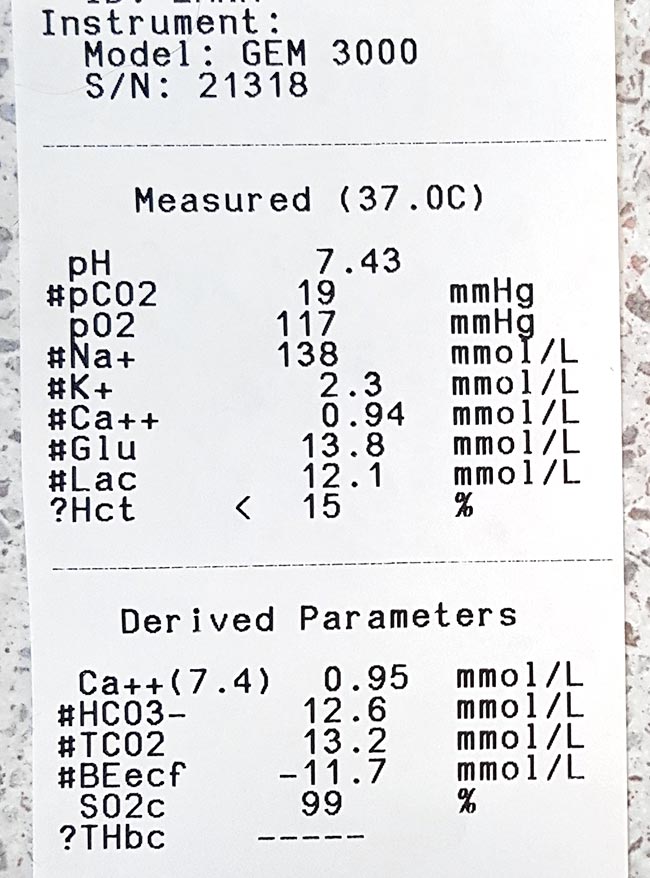

iCa is the biologically active fraction of calcium and is not to be confused with total calcium (tCa). A lack of concordance exists between the two. Adjustment formulas are inaccurate, even with the correction of the tCa to serum total protein or albumin concentration, and should not be used to predict iCa.

The normal reference range for iCa in dogs is 1.2mmol/L to 1.5mmol/L; in cats, it is 1.1mmol/L to 1.4mmol/L.

Function

Calcium is essential in maintaining normal physiological processes in the body. iCa regulates:

- vascular tone

- myocardial contraction

- homeostasis

In addition, it is needed for:

- enzymatic reactions

- nerve conductions

- neuromuscular transmission

- muscle contraction

- hormone release

- bone formation

- resorption

In critical patients, particularly those with severe trauma or sepsis, vascular tone and coagulation is particularly important. For this reason, iCa is tightly kept in a narrow range and regulated by the interactive feedback loop that involves iCa, phosphorous, parathyroid hormone, calcitriol and calcitonin.

Diseases and causes

Diseases commonly associated with low iCa in dogs and cats include:

- acute kidney failure

- acute pancreatitis

- diabetic ketoacidosis

- eclampsia

- ethylene glycol intoxication

- protein-losing enteropathies

- sepsis

- trauma

- urethral obstruction

- parathyroid diseases

- tumour lysis syndrome

Situations altering the fraction of extracellular calcium seen on a regular basis include:

- acid-base disturbances

- lactic acidosis

- protein loss or gain

- increased free fatty acids

Iatrogenic causes include:

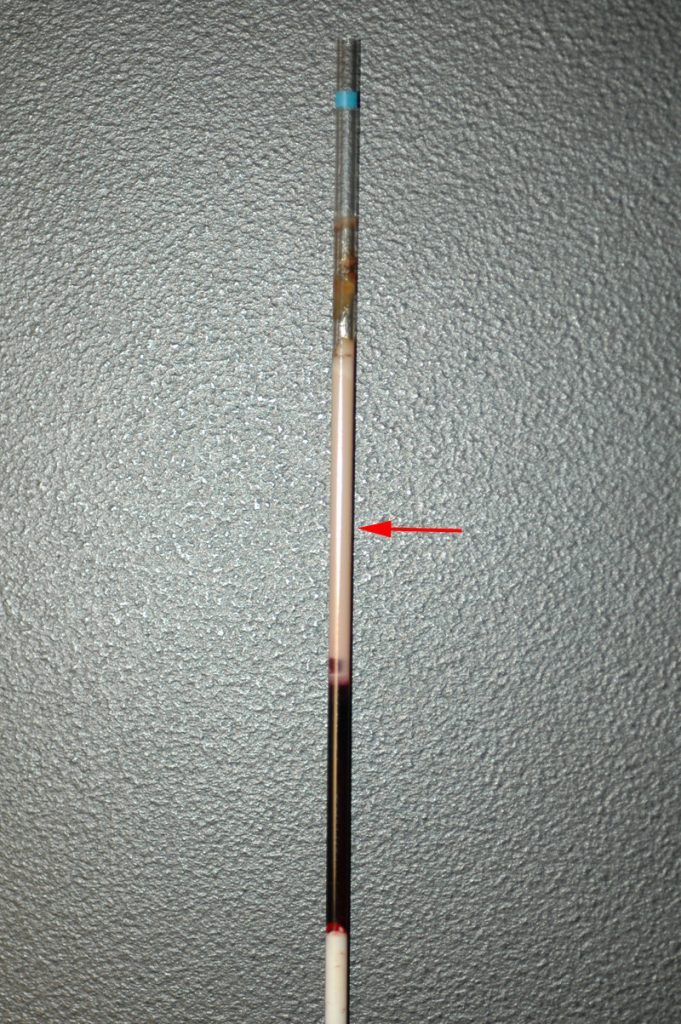

- citrate (anticoagulant) administration during blood transfusions

- phosphate

- bicarbonate

- sulfate administration

Low iCa can also develop during cardiopulmonary resuscitation, quickly declining with increased duration.

- Part two will go into more depth regarding the most common causes of low iCa that require acute treatment, the treatment involved, controversies surrounding treatment of non-clinical low iCa, and prognostic indications.