Part one of this series covered the stages of labour and indications dystocia is present.

Once the bitch presents to the clinic, a few basic diagnostic checks need completing to determine the status of the bitch/queen and the fetuses.

Physical examination

The first is a thorough physical examination, starting with the bitch or queen:

- Demeanour, hydration status, vital signs, mucous membrane colour, capillary refill time and temperature are important.

- Pregnancy anaemia is not uncommon; however, for patients with a haemorrhagic discharge, it is important to know their cardiovascular status.

- A thorough abdominal palpation should be carried out to assess comfort level and palpation for the presence of fetuses. Palpating fetuses can be difficult and cannot confirm if no fetuses are present.

- A digital vaginal examination should be performed. Feathering response – also known as the Ferguson reflex in human medicine – is the neuroendocrine reflex where the self-sustained cycle of uterine contractions is initiated by firm pressure on the dorsal aspect of the vestibulovaginal wall. If this is absent, the patient is unlikely to progress with the parturition unaided.

- Palpation of fetuses in the canal can help decide whether surgical management is required. Obvious fetal malposition, malposture or malpresentation, or fetopelvic disparity, will be indications of caesarean. Abnormal pelvic diameter is also another reason to not proceed with medical management. To confirm these suspicions, abdominal radiography is required.

- Radiographs will also help determine the number of fetuses to be expected, the signs of fetal death (presence of gas surrounding the fetus) and aforementioned fetomaternal abnormalities. I always repeat radiographs after the expected number of neonates is passed, to make sure I have not miscounted at the start.

Ultrasound

Dogs:

- normal – 180 to 220 beats per minute (bpm)

- Stressed – 160bpm

- Real concern – less than 160bpm

Cats:

- normal – more than 220pbm

- fetal stress – less than 180bpm

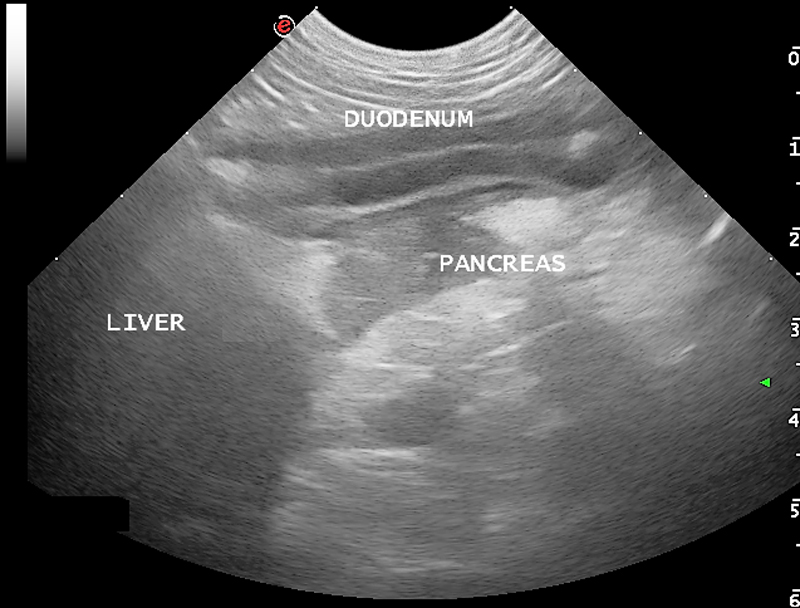

The second important diagnostic tool is ultrasound.

Fetal heart rates are good indicators of fetal stress. Some heart rate ranges that can help provide information about the status of the fetuses are detailed in Panel 1. These ranges vary between sources, but are good guidelines.

Ultrasounds can also help visualise the maturation status of the fetuses. At-term fetuses should have normal hepatic, renal and intestinal development. Intestinal peristalsis should be evident in at-term fetuses.

Other diagnostics

Other diagnostics may be indicated for patients, depending on the status of the bitch/queen:

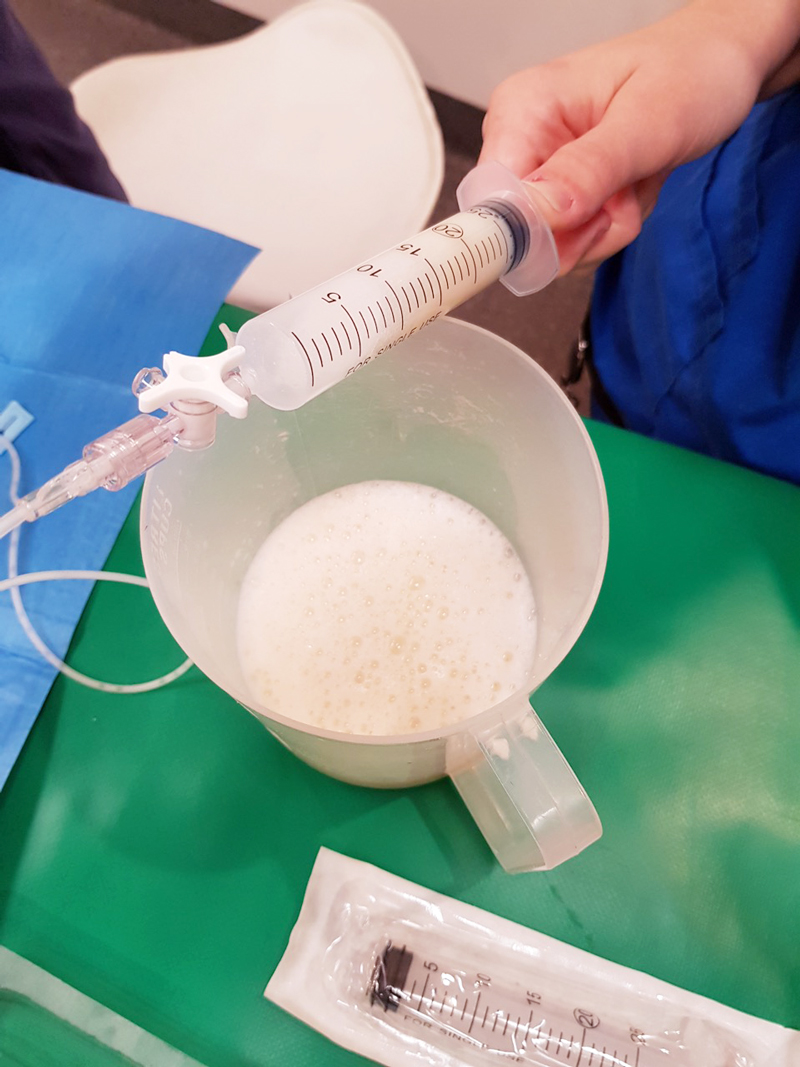

- If the patient is stable, but dystocia is present, a minimum database would include PCV/total protein, electrolytes, glucose, ionised calcium, lactate and acid-base balance.

- Serum ionised calcium levels are important, as they influence the strength of contractions and how much supplementation is required.

- Hypoglycaemia needs to be ruled out as a cause of dystocia, especially when large litters are involved.

- If the patient is unstable or systemically unwell, include complete blood count, blood smears and biochemistry.

- Physiological pregnancy anaemia can be present. The presence of regenerative response can help differentiate this from acute haemorrhage.

- Abnormal leukocyte panel, especially with the presence of degenerative left shift, can indicate the presence of an infection – especially if toxic changes are present in the neutrophil.

Part three will briefly look at the medical management of dystocia and when surgical intervention is required.