We frequently field telephone calls from owners concerned about their pet being intoxicated or having access to a toxic compound.

These are the list of questions I always ask owners:

What is your pet doing?

The main reason I ask this question first is to determine if the pet’s life is in danger. If the pet is seizing, collapsed, neurological, bleeding or having difficulty breathing then they need to come into practice immediately.

What led to the suspicion of toxic exposure?

This can help provide useful background information.

What is the product?

In some situations, owners can tell you accurately over the telephone what they think they have been exposed to.

Asking them to bring the packaging, and whatever is remaining of the toxin, with them can help determine a possible dose they have been exposed to.

When did this occur?

A timeline, and when they think the pet could have been exposed to the toxin, is critical as it can help put presenting clinical signs into perspective.

I always ask if they could have had prior exposure to the toxin. An example where this may be important is with rodenticides.

What have you done in response to this?

Owners may have tried to address the situation themselves, using information gained from the internet.

Attempts to induce emesis can also make pets incredibly ill and result in neurological signs.

Have they passed faeces or vomitus with the toxin?

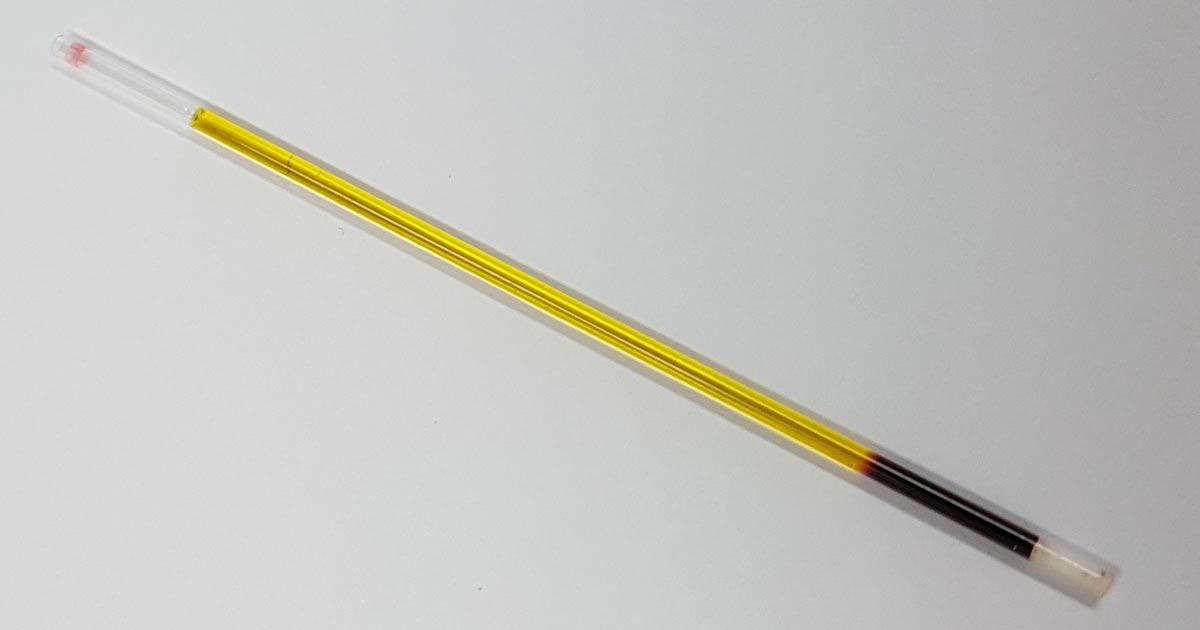

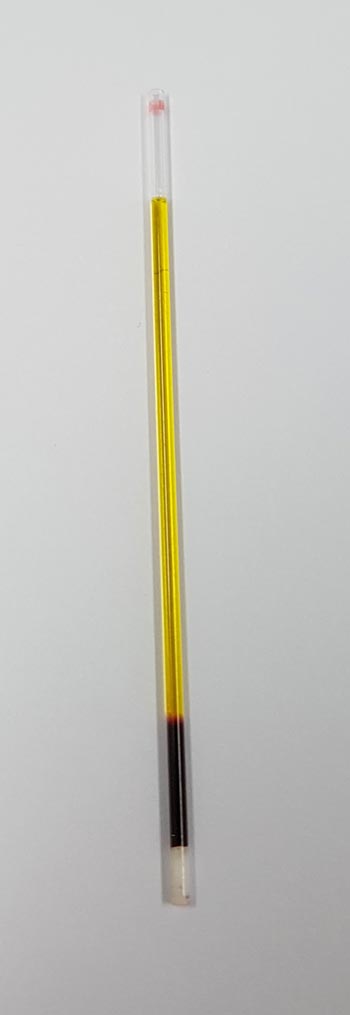

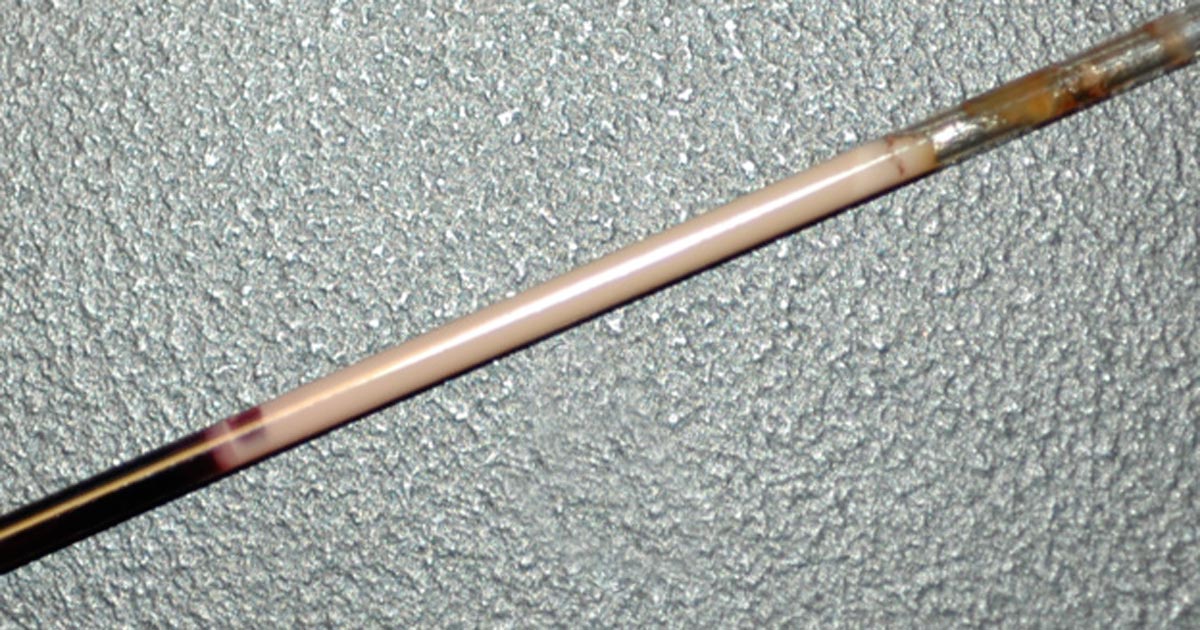

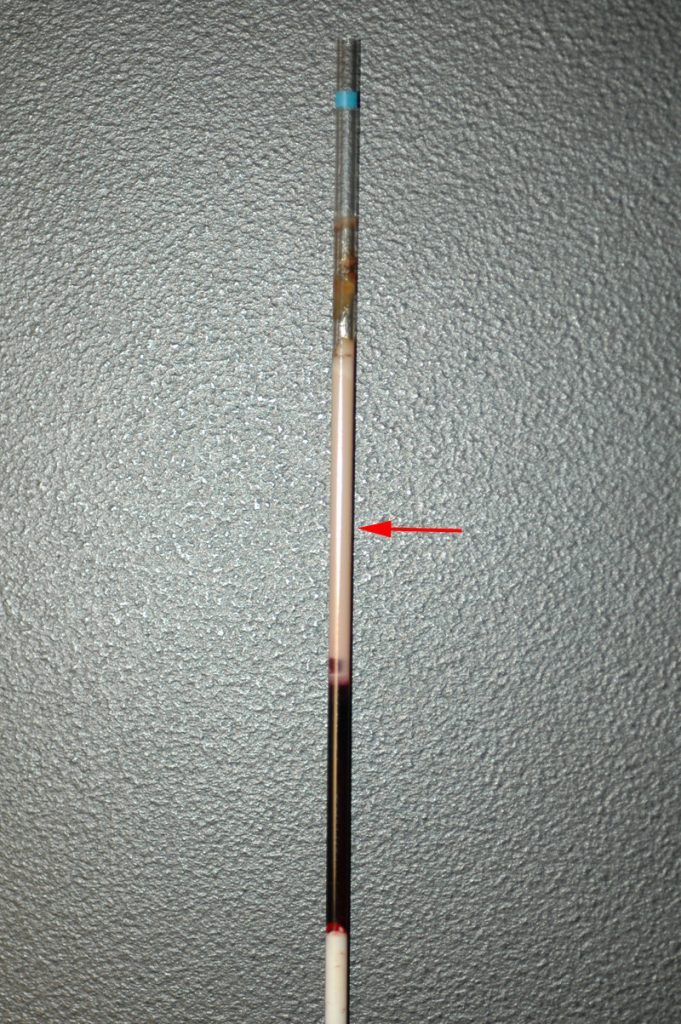

If the answer is yes, ask them to bring the pet into the practice. This can help identify the toxin; some baits are coloured and can easily be seen. These samples may even be able to be sent away for further testing.

Do you have any other pets that may have also had access to the toxin?

Other pets that may have had access will need to be seen in practice as well. A classic example is a multi-dog household where one pet is the scavenger. Owners may neglect to inform you their other pets may have been the culprits, but did not because they assumed it was the one with the history of being a scavenger.

Next week, we will cover the decontamination steps owners can carry out at home.

The process is quick – 10 to 20 seconds

The process is quick – 10 to 20 seconds