Fleas and ticks are both direct agents of disease and specialised vectors for transmission of some of the most economically important and devastating infections affecting the health of companion animals and their owners worldwide. Effective management of flea and tick infestations requires early recognition of the infested pet, application of treatment to kill the pests on the pet and containment of environmental stages. Successful implementation of these measures is increasingly complex, with important roles played by veterinary professionals and pet owners that are critical to protecting and sustaining pet health and welfare.

Unfortunately, the high risk of flea and tick infestation to pets and pet owners is not paralleled by the expected level of awareness and compliance by pet owners. Building partnerships are essential to make progress; however, getting many pet owners to collaborate can be slow and frustrating. Therefore, it is crucial to create the advocacy needed to communicate accurate and timely information to the pet owners, stay equipped with the latest scientific knowledge to increase awareness, and to effect behaviour change and engage the community of pet owners.

In this article, the importance to appreciate the significant economic and health impact of flea and tick infestation on both pets and their owners is discussed. Also, the reasons underpinning the lack of awareness of some pet owners regarding the need for year-round protection, and possible solutions to tackle this challenge, have been presented.

Raising awareness of the need for flea and tick prevention in dogs and cats is more important than ever, with infestations able to cause a wide range of skin problems in both pets and pet owners.

Control of these common pests is essential, not only to maintain the health and welfare of the pets, but also to protect people from unnecessary suffering, and from the potential transmission of serious zoonotic infections.

Our understanding of diseases caused by fleas and ticks has grown considerably in the past decade. However, some pet owners still have not taken the problem of flea and tick infestations seriously. Probably, these pet owners are not aware of the negative health consequences repeated flea and tick bites can cause, and may just consider ectoparasitic infestations to be less serious than other health problems.

Results of an epidemiological survey about the opinions and actions of dog owners in the US showed their adherence to flea and tick treatment fell short of vets’ instructions (Lavan et al, 2017). This problem is not the responsibility of pet owners alone, it lies on the shoulders of other stakeholders, such as veterinary professionals and drug companies. In an effort to mitigate this problem, some progress has been made on both the professional (increasing awareness campaigns) and industrial (availability of many effective products) levels. Despite these efforts, we are still far from achieving an optimal control of flea and tick infestations.

In this article, the adverse clinical consequences caused by fleas and ticks are discussed, together with proposing some ideas to improve the treatment and prevention strategies of these infestations.

Fleas and ticks are real dangers

Companion animals have always suffered from ectoparasite infestations – particularly fleas (Figure 1) and ticks (Figure 2). Infested animals often experience severe irritation and sensitivity reactions. Fleas are the most prevalent ectoparasites infesting dogs and cats, with around 1 in 10 dogs and 1 in 5 cats having fleas at any given time. In recent years, considerable media campaigns have raised awareness of the risk of flea infestation. According to the UK PDSA Animal Wellbeing (PAW) Report 2017, 82% of dogs, 82% of cats and 13% of rabbits were treated for fleas.

Some pet owners, however, remain unaware of the potential for unprotected pets to pick up fleas from the garden and park, or wherever wild animals, stray cats and untreated animals may have been. Even indoor pets can be affected by fleas carried into the home on clothing or other materials, or from stray cats. Pets can be infested with various flea species. The cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis), for instance, can infest cats and many other animals, such as dogs, rabbits and hedgehogs. The dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) is found on dogs, but less often on cats, especially in more temperate climates. The human flea (Pulex irritans) can infest both humans and pets.

Owners should also realise their pets can easily pick up ticks by walking in long grass and vegetation where ticks wait to latch on to the next host. They climb one to two feet from the ground into the shrubs or grass and wait until an animal brushes by that they can crawl on to. But it is not only pets that can get ticks; humans can get them too. In recent years, the geographic range of many tick-borne diseases has expanded and several novel infections have been described. Tick bites spread Lyme disease and other infections to pets and people, so employing effective preventive treatments is more important than ever.

What if it’s not treated properly?

Owners need to understand the importance of keeping their pets protected. A greater understanding of the veterinary, medical and public health impacts of flea infestation will help the majority of pet owners to appreciate this. Flea infestations can lead to intense itching, pruritus and scratching, leading to inflammation, fur loss and secondary bacterial infections. Animals with flea allergy dermatitis (Elsheikha, 2012) – due to a sensitivity reaction to antigens present in flea saliva and/or dirt – can develop irritation and inflammation from a single bite, while heavy infestations in puppies and kittens can lead to life-threatening anaemia due to feeding on the pet’s blood.

Fleas carry the risk of tapeworm infestation because tapeworms spend part of their development inside fleas. Fleas are the intermediate host for the dog and cat tapeworm Dipylidium caninum. Controlling fleas will also prevent tapeworm infections, which can also affect humans – particularly children.

Fleas may also carry blood-borne infections, such as Bartonella henselae, which can cause flu-like symptoms in people. Other blood-borne pathogens that have been isolated from fleas include Rickettsia felis and Haemoplasma species (causing anaemia in cats) and Yersinia pestis (causing plague, a life-threatening infection if not treated promptly). More information about the risk of fleas and flea-borne infections have been summarised in a round-table discussion (Bourne et al, 2018).

Ticks can also compromise the health of the affected animal through multiple mechanisms. Blood feeding and engorgement of many female ticks can cause severe anaemia and immunosuppression. Secondary bacterial infection of bite sites can lead to skin pathologies or pyogenic lesions. Toxins secreted in the saliva of certain ticks can cause tick paralysis.

Due to being haematophagous (feeding on blood from vertebrate animals), ticks can vector many serious disease-causing pathogens (Elsheikha, 2016a). Two examples – canine ehrlichiosis due to Ehrlichia canis and canine babesiosis due to Babesia gibsoni and Babesia canis – can cause significant ill health in dogs. Infections may progress to chronic disease, resulting in immunosuppression and pancytopenia (in case of ehrlichiosis), or haemolysis and shock due to multi-organ ischaemia (in cases of babesiosis).

Fortunately, babesiosis is rare in British dogs, with most cases being acquired abroad. However, the detection of a cluster of dogs with babesiosis in Harlow in the winter of 2015/2016 (Phipps et al, 2016), and subsequent cases in Romford in 2016 and 2017 – some of which had not travelled abroad – has raised concerns babesiosis may become endemic in the UK (Wright, 2018).

A survey detected Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Bartonella species (including B henselae and B clarridgeiae), haemoplasma species (Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum, Mycoplasma haemofelis and Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis), Hepatozoon species (H felis and H silvestris) in ticks collected from cats in the UK (Duplan et al, 2018). Ticks are also responsible for the spread of zoonotic diseases to humans, for example Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, tularemia and rickettsial diseases.

Treatment options

It is essential all veterinary staff understand the indications and adverse effects of the available products to make sound decisions on their suitability for each pet. This requires all staff to have a good understanding of flea life cycles so they can advise owners on correct treatment of environmental flea and larvae contamination.

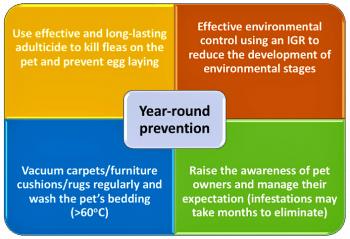

Anti-flea products are divided into adulticides (kill adult fleas) and insect growth regulators (IGRs), which prevent the development of the eggs and larvae. The main groups of insecticides against fleas have been summarised in an article (Elsheikha, 2017). The need to use host-targeted and environmental insecticides to eliminate flea stages in the pet’s environment has led to the development of products combining an adulticide with an IGR (for example, methoprene or pyriproxyfen) or insect development inhibitors (for example, lufenuron). These, along with environmental measures, can achieve an integrated flea control programme (Figure 3).

IGRs mimic an insect growth hormone that prevents immature stages from developing. Lufenuron prevents the larval teeth from hardening so the larva cannot hatch from the egg. IGRs may be used directly in the environment for existing infestation, such as in the form of a spray or fogger. IGRs can also be used in combination with an adulticide on the animal to prevent infestation from occurring by disrupting the flea’s reproductive cycle. Although most adulticides will kill fleas within one day prior to egg laying, owner compliance is generally poor, and some fleas may survive for long enough to lay eggs at the end of the treatment interval. Therefore, the use of an IGR at that stage will render eggs that have been laid unable to cause infestation.

The best treatments against ticks rapidly kill them before they bite, reducing the transmission of disease. A number of anti-tick products exist that can be used to reduce the risk of exposure of pets to ticks. The choice of product must be based on lifestyle factors, previous tick exposure, living in or travel to an endemic region or country, owner affordability, preference (tablet, collar or spot-on) and other kinds of concurrent drug treatments.

Some products contain pyrethroids, which have a tick-repellent (prevent ticks from taking a blood meal) as well as having insecticide and acaricide effects (Elsheikha, 2017). A study by Goode et al (2018) reported the promising potential of turmeric oil suspension as a tick repellent. Tick treatment of pets entering the UK, although not obligatory, is still needed to protect travelling and resident pets. A Lyme disease vaccine is available and this should be discussed with pet owners based on the individual risk to the animal.

Cats can develop toxicity if a canine permethrin product is applied inappropriately, or via secondary contact with a dog treated with a spot-on product containing permethrin. Hence, it is advisable to avoid the use of permethrin-containing products on a dog that shares a home with a cat. A collar that contains 10% imidacloprid and 4.5% flumethrin has been developed for use on dogs and cats. This product contains both repellent and insecticidal properties and has been shown to reduce tick counts by at least 90% and flea counts by at least 95% for a period of at least seven to eight months in cats and dogs under field conditions (Stanneck et al, 2012a; 2012b).

All licensed macrocyclic lactone preparations are safe – even for MDR1 (avermectin-sensitive) dogs, which are often collie-type breeds. However, these dog breeds are more sensitive to overdoses and it is important to avoid giving more than one of these avermectin-containing products. These substances bind with p-glycoprotein transporters, hence their use with other drugs using the same targets (for example, digoxin and doxorubicin) can enhance toxicity.

Proactive counselling

The persistence of fleas in the environment and on pets following treatment has raised concern of insecticide resistance. However, although resistance genes have been found in laboratory strains of flea, some flea products (for example, fipronil, selamectin and spinosad) have been shown to remain efficacious (Bass et al, 2004; Dryden et al, 2013). The perceived failure of flea treatment can be due to a number of factors. These include:

- Not treating all animals – if all susceptible animals are not treated at the same time, this creates the opportunity for fleas to breed.

- Not treating the environment – adult fleas encompass 5% of the total flea population. Thus, without control of environmental stages, some flea infestations may take months to eliminate.

- Lack of management of expectations – a heavy infestation of fleas may take at least three months to eradicate, even when environmental measures are implemented (Dryden et al, 2000).

- Not treating pets frequently enough – often because the advice provided is inaccurate, misinterpreted or not followed.

It is important to quickly identify causes of treatment failure (due to lack of compliance or other reasons), and to initiate and monitor the treatment’s success. More intensive monitoring and treatment may be necessary in animals with flea bite hypersensitivity to achieve a successful outcome.

Protective measures should be adopted to control ticks, such as avoiding tick habitats – including heavily wooded and grassy areas, using repellents, and frequent tick checks (at least one check per day) to pick up and remove ticks with a tick removal device or fine-pointed tweezers, before they can transmit disease.

Collected ticks should be identified using identification keys (for example, www.bristoluniversitytickid.uk). Also, dog owners and members of the veterinary profession can send found ticks to Public Health England’s Tick Recording Scheme or the Big Tick Project (www.bigtickproject.co.uk) for species identification. Even though the average transmission time for Borrelia (the agent of Lyme disease) and Babesia is one to two days, transmission can occur within 16 hours and the minimum attachment time for transmission of infection remains unclear.

It is possible Rickettsia and Ehrlichia can be transmitted quickly (within three to four hours). Transmission is correlated to the duration of tick attachment, and it is advisable to use products that kill or repel ticks as quickly as possible to reduce the risk of disease transmission. Always inspect the entire body for ticks after handling dogs and remove by pulling them straight out with tweezers or a specially designed tick-removal tool. Travellers to tick-endemic areas should be advised to use proper prophylactic medication before travel and continued after return.

Improve owner compliance through partnership and communication

Parasite preventive medicines are only effective in protecting the treated animal when used according to appropriately prescribed recommendations. Therefore, regardless of veterinary advice, failure of owner compliance will reduce the success of any ectoparasite treatment recommendations provided to the client (Bourne et al, 2018). This might also lead to a lack of pet owner confidence in the recommendations, a reduction in spending and potentially adverse consequences to animal health.

Any slight improvement in enhancing pet owner compliance can make a previously unattainable goal possible. Therefore, improving compliance is crucial by focusing on the most effective, feasible and sustainable interventions, and this can be achieved in synergy with other intervention elements (Biggle, 2016; Elsheikha, 2016b). The key is to identify elements that are highly effective and scalable to reach the largest number of pet owners, encompass a broad demographic composition, and include wide geographic areas that can be sustained over a long period. Effective communication can lead to behaviour change, but, more importantly, it can lead to increased commitment by pet owners and the effectiveness of ectoparasite control programmes by engaging pet owners and by contributing to a change in their perception of this important issue.

With the advent of the internet, social media and other communication technologies, information has become available from more sources than ever, although some is incorrect or potentially misleading. Pet owners, therefore, should be directed to the most credible and up-to-date information source online. People are different and different pet owners need to be presented with scientific evidence in various ways to achieve the intended impact.

Conclusion

During the past two decades significant progress has been made in the development of ectoparasiticides to treat and control fleas and ticks. The market is full of products, giving owners and practices flexibility in choosing the most effective product to suit their needs and expectation. Most flea and tick products contain one or more ingredients that have insecticide and/or acaricide effects. Also, several combination products are available that cover fleas and roundworms. Ectoparasiticides can be used to kill parasites already on the animal’s body and can kill newly acquired parasites to prevent reinfestation.

The rapid transmission times of rickettsial diseases and the presence of the protozoan Leishmania infantum in southern Europe, makes it necessary to use tick and sandfly repellents when travelling to countries where these pathogens are common. Ectoparasite control will continue to rely on ectoparaciticides, providing clinicians with more and effective tools to tackle the challenge of flea and tick infestations. By providing accurate, timely, and convincing information that includes evidence-based data on the efficacy of treatment, vets can increase their credibility, and minimise confusion and distrust with their clients.

Finally, vets must make professional and business judgements to ensure the requirement for meeting client expectations, improving pet health and maximising the practice revenues, without skewing practice policy and imposing unnecessary burden on their clients.

- The author declares the article was written in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.