With education secretary Gavin Williamson recently coming forward to suggest that universities should reduce their fees if they choose not to return to face-to-face teaching, the question is being asked once again if online teaching can really hold its own against the real thing?

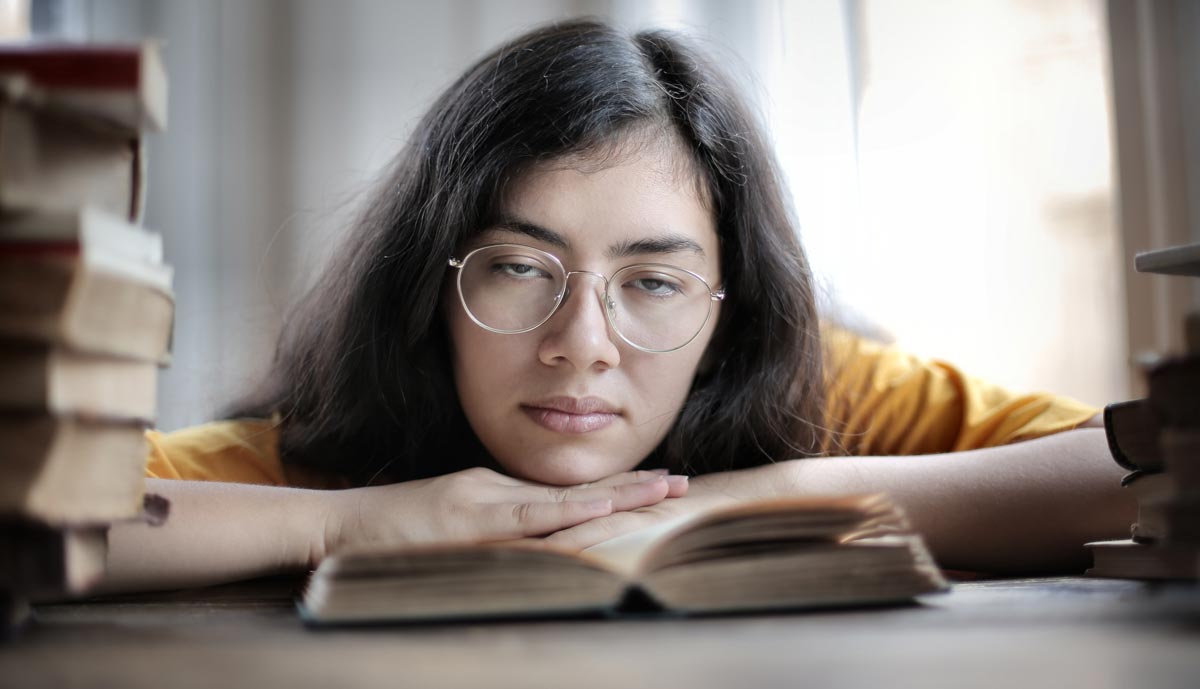

Loneliness

One of the main trials of the vet course has always been its difficulty. It’s hard, both academically and at times emotionally (and, when you’re called upon to tip a sheep, sometimes physically), there’s no getting away from that.

Online learning doesn’t reduce the course’s difficulty, but it does have the potential to exacerbate it, especially for those with attention deficit disorders who benefit from a more tangible learning environment.

The online platform is also unable to replicate that feeling of camaraderie you get from the live experience. If you can see your coursemates struggling on a particular topic you are also struggling with, then at least you’re reminded that you’re all in the same boat; but when you’re struggling to comprehend a lecture in your room by yourself – day in, day out – it can be easy to feel that maybe you’re the only one having trouble, and that you’re falling behind the rest of the herd.

The little things

All vet students and new grads will still remember the horrors of 9am lectures. Let’s be honest, nobody actively looked forward to them – especially, I’m sure, my fellow Bristol students, for whom struggling your way up one of the many formidable hills in gale force winds and torrential rain was a rite of passage.

Saying that, you always end up missing what you don’t have, and while a classroom of shivering 20-somethings with 150 coats attempting to dry on the one single lecture hall radiator may not sound like the epitome of a good time, it’s just one of the little things that builds a person’s university experience.

There will be highs and lows, good days and bad days that all make up the tapestry of academic life. While some may prefer to listen to recorded lectures in bed, I think being given the choice is inherently necessary.

Isolation

There are also an often-unheard body of students, for whom those lectures represented the only opportunity to interact with people and have space to learn. Sadly, not everyone at university has a living situation that supports their learning, whether it’s a disruptive home life, unreliable Wi-Fi, or any other number of things.

I don’t think this is something that universities fully take into account, and I feel especially sorry for international students paying incredibly high fees while entirely unable to explore their new surroundings or get the experience they were advertised. For those who study far from their homes and families, online learning has the potential to be incredibly isolating. I know my own mental health has certainly suffered as a result, and I’m sure I’m not alone.

Screens, screens, screens

When I was little, my mother used to tell me that if I stared at a screen for too long my eyes would turn square, and although I’ve since dismissed it as a method to get me to tidy my room instead of watching Power Rangers, I now fear it may be true…

I know that may sound a little “six of one, half a dozen of the other” seeing that in-person lectures use projectors and laptops as well, but I truly believe online learning massively ramps up your screen time. Even in 3-hour long lecture blocks, we would still be given short breaks between lecturers, you’d turn to talk to your friends and maybe focus more on the lecturer than the words on the slides.

When your only way to learn is via your laptop, and your only way to recharge after those lectures is also your laptop (Netflix, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and so on), you could easily pull a nine-hour shift sharing predominantly at a screen. Excessive screentime has been linked to postural-injuries, back and neck pain, negative impacts on sleep and emotional states, eye strain and migraines.

Imperfect fit

Obviously, everyone’s experience of the past two years has been unique and, as such, I’ve found that my fellow students tend to have mixed opinions of online teaching platforms or “blended learning” (when the majority of your work is done online, but augmented with a smattering of in-person teaching, perhaps once a month).

Some of my cohort really enjoy having all of our lectures at the touch of a button, while others have struggled with the lack of contact with their peers and mustering daily motivation.

Personally, I can see both sides of the coin, but I think it needs to be accepted that while there are merits to both the new and old system, the two are simply not comparable – and like every teaching system, neither are a perfect fit for every student.