I’ve written before about omnicompetency, but the word is mostly used in the sense of vets being able to work in mixed practice and tackle the veterinary care of horses, dogs, cats and farm animals in the same day – certainly, the first thing to come to mind would not be a reindeer.

However, on my recent equine placement, the staff were met with quite the challenge when a reindeer was referred in.

With a history of acute coughing/regurgitation, the reindeer in question had a suspected food impaction in the cranial oesophagus. Conscious radiographs and an ultrasound scan (he was a very well-behaved reindeer) confirmed suspicions of foodstuff, but it didn’t seem to be in the oesophagus.

Collaborative anaesthesia

The equine team – with help from one of the farm vets and some phone calls to other colleagues and practices that had dealt with reindeer before – came up with an anaesthetic protocol and proceeded to surgery.

The reindeer was induced with ketamine and xylazine before a gastroscope was used to try to visualise the larynx and trachea.

There appeared to be a diverticulum or outpouching from the oesophagus at the level of the larynx, which is where the food impaction had settled.

This discovery triggered a discussion as to whether our findings could be normal in some reindeer – similar to the Zenker’s diverticulum in people – since its appearance suggested a congenital, rather than acquired, defect.

A gastroscope was used to aid placement of an endotracheal tube and the reindeer was, subsequently, maintained under anaesthesia with isoflurane. He was positioned carefully in consideration of the rumen and ventilated throughout the procedure, which was to incise into the pouch using a lateral approach and remove the impacted food material.

Back to his reindeer games

He recovered well from the anaesthesia and was happily bounding around a paddock before long, eating some specially imported moss provided by his owner.

Reindeer aren’t something you’d expect to see every day in practice, but it was a great example of how veterinary knowledge can be adapted and applied to new situations, with the added benefit of working together with others with varying levels of experience to come up with a solution.

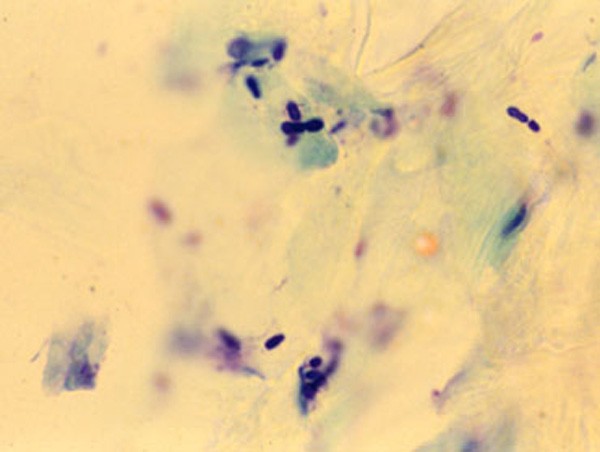

![Cytology of a mast cell tumor from a Labrador retriever at a magnification of 1,000x. By Joel Mills (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.](http://www.vettimes.co.uk/app/uploads/2014/06/Mast_cell_tumor_cytology_2-300x284.jpg)